General David Hunter replaced General Franz Sigel on May 21, 1864, just six days after the Battle of New Market. General Ulysses S. Grant immediately ordered Hunter to apply scorched earth policies, if necessary, in his advance up the Shenandoah Valley. His instructions were to march through Staunton, Charlottesville, and then on to Lynchburg destroying the Virginia Central railroad such that it was “beyond possibility of repair for weeks.”

Hunter began advancing his army from its camp at Belle Grove, near Middletown, on May 25. By the following day, his army had arrived at Woodstock, and by May 30, Hunter had reached New Market. Here he would, for the most part, cut himself free from his supply line and begin living off the land.

General Hunter would remain at New Market until June 2nd, at which time he broke camp and headed for Harrisonburg. Along the way he met with very little resistance from Confederate forces. Hunter’s scouts informed him on June 4, however, that General John Imboden’s forces were dug in on the south side of the North River at Mount Crawford. Imboden had concentrated his forces there, intent on obstructing a direct approach to Staunton. To avoid a frontal assault across the river, Hunter decided he would move east around Imboden’s right flank by passing through Port Republic. He would employ a pontoon bridge there to force a safe crossing of the South Fork.

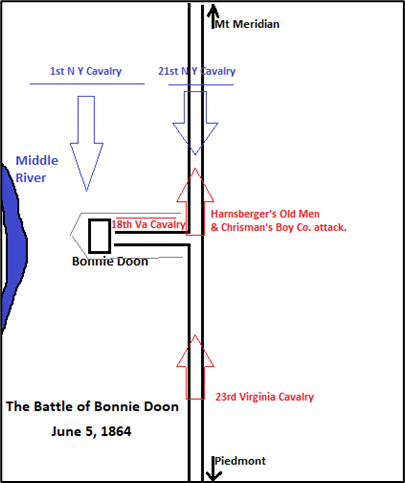

Reacting to Hunter’s move, General Imboden shuffled his headquarters from Mount Crawford to the Mount Meridian area so that he could continue to contest the advance of Hunter’s Army. With him he took Harnsberger’s Old Man and Chrisman’s Boy Cavalry Companies. These forces were now operating under the command of Captain T. Sturgis Davis. They were to stay out in front of Hunter’s army in order to resist his continued advance up the valley. Meanwhile, John Mosby and other rangers would strike Hunter’s flank and rear.

On June 4 the 18th Virginia Cavalry set up camp near Mount Meridian, six miles south of Port Republic. A second contingent went into bivouac that same day a mile to their south on the Bonnie Doon Plantation. The estate was situated on readily defended high ground. Here Chrisman’s Boy Company, and Harnsberger’s Old Men were joined by Sturgis Davis’s Marylanders, and John Opie’s and Henry Peck’s mounted reserves from Augusta County.

Field in the foreground is spot where Rebel Cavalry camped at Bonnie Doon.

The following morning the 1st and 21st New York Cavalry were up early and moving by 4 am. The weather was foggy, with a drizzling rain, as Union troopers trotted south toward the settlement of Mount Meridian. The 1st New York was leading the march with the 21st trailing some distance behind.

After two hours on the road Federal scouts spotted “the enemy in force.” They had collided with the 18th Virginia Cavalry. The New Yorkers quickly formed line and prepared to attack. “Skirmishers were thrown out in front and flankers to the right and left.” Major Timothy Quinn pushed Company C into line in the woods on the right and Company A to the left. The remaining companies were deployed into column in the center.

Hotchkiss Map showing the region between Port Republic and Piedmont.

The attackers were soon slowed by a wooden rail fence which obstructed their path. Troopers were forced to dismount and tear down the impediment. When they remounted, they were surprised to “see immediately in front of them a broad rounded hill filled with the enemy.” The spectacle spawned a momentary pause on the part of the assailants.

The New Yorkers, remounting their horses, pressed forward once more. Regrettably, they were “forced to halt once again and became a mark for the Confederates on the hill. They were taken at a disadvantage.” Lieutenant Isaac Vermilya was presently shot and fell from his horse. “There seemed to be no one just there to give the command to deploy and charge.” Instead, “they held their ground and promptly and continuously returned the enemy’s fire.”

An unnamed Confederate officer reacted quickly. “Charging with uplifted sabre (he) led a charge down the slope of the hill with such vigor that these companies were forced back into the woods.” There was complete chaos on the field of battle. In the “fierce saber fight” that ensued the New Yorkers were repulsed.

The 1st New York was not ready to give up. They quickly regrouped and initiated a counterattack. The pursuit of the retreating Confederates was swift. The 1st New York’s Lieutenant Edwin Savacool’s horse got out of control and bolted into the Confederate lines. Fortunately for the Lieutenant he was wearing his rubber coat. Reflexively he began to mingle with the enemy and, as a result, remained unobserved. He later gained his freedom in the midst of a second attack by his regiment.

The fire from the 18th Virginia was devastating to the 1st New York. “Sergeant Buss, George Mason, and twenty or more of other companies were wounded in probably less than five minutes. Lieutenant Clark Stanton was shot in the thigh.” Thomas Gorman while attempting to jump a rail fence fell with his horse and was trapped under the weight of it. A couple of Confederates captured Gorman, only to be forced to release him moments later due to the Union counterattack.

Fortunately for the Union cause, Colonel William Tibbits’ 21st New York Cavalry Regiment arrived at this moment with four hundred additional troopers. Tibbits was quick to react, throwing his men immediately into the melee. Once again, the fighting became close and deadly. It was “saber to saber.”

Colonel Tibbits, finding himself in the middle of this savagery, had a very close call while he was riding his beloved war horse “Old Bill.” In the close fighting he received a wound to his “saber hand.” Forced to pull his revolver, he began to trigger it at the enemy at close quarters. Presently, Tibbits was attacked by a Confederate swinging a saber directly at him. Tibbets attempted to fire his gun and though the cap flashed the powder did not ignite. “As the rebel cavalryman swung his sword Tibbits threw himself over on one side of Bill’s neck and gave him the spur.” Old Bill leapt over a fence leaving the rebel cutting air with his sword.

The 21st New York, Chrisman’s Boys and Harnsberger’s Old men collided at the base of the hill in the distance.

As the 21st New York renewed its assault, the 18th Virginia’s line broke and they began retreating toward Bonnie Doon. The 1st New York was in close pursuit to the west while the 21st New York was pounding up the road toward the farm on the east. Most of the 18th Virginia “made the leap over the plank fence on the north side of Bonnie Doon Lane only to find they did not have room enough to get momentum to clear the fence on the south side.” These men were trapped, as troopers from the 1st New York galloped up to the fence and began to pour fire into the milling Confederate horsemen.

Sketch of the Battle at Bonnie Doon. (Author Microsoft Paint)

Imboden quickly realized that he must call out his reserves. Next up were Chrisman’s Boys, a cavalry company made up of 16- and 17-year-old teenagers. With little or no training this would be their second call to combat in less than a month. Also available was Harnsburger’s Old Man Company, a cavalry band consisting of men 45 to 50 years of age. This would be their first fight.

Spread among these two companies were many young adults and seniors, each with lives to live and stories yet to tell. John Hooke was one of them, a member of Chrisman’s Boy Company. He had grown up in the hamlet of Cross Keys where he had celebrated his seventeenth birthday just one month prior. Two of John’s older brothers had already perished from injuries suffered at the Battles of 1st and 2nd Bull Run. John’s 46-year-old father, William, too old to join the regular army, had recently attached himself to Harnsberger’s Old Man Company. Both sat astride their horses on that rainy June morning, undoubtedly stealing glances at one another, each wondering if either of them would live to embrace each other, or see their home, ever again.

The moment had come, and Captain Davis ordered his reserves into the fray. The combatants were now called upon to aid in the 18th Virginia’s escape from the fenced in enclosure surrounding Bonnie Doon. The 21st New York, pounding south along the East Road, was threatening to pass to the rear of the 18th. If successful it would trap these men, allowing them to be either captured or killed.

Chrisman’s Boys and Harnsberger’s Old Men “thundered down the road in a ‘reckless thrust’ and hit the head of the New York Column with a crash.” “It was hand to hand combat with sabers and pistols.” Captain Harnsberger was quickly shot in the left leg and arm. In short order more than half of the men from both companies were dismounted in the brutal fighting.

A Cavalry Charge (Edwin Forbes)

Chrisman’s Boys were crushed by the impact of the assault. The youngsters were in a stand up fight against veteran New York cavalrymen. The sabering was horrific and the young men were at a major disadvantage. Though better armed than they had been in their first fight at New Market on May 13, many still did not have pistols or swords. Colonel Chrisman, witnessing the carnage, quickly inserted himself into the melee, firing his revolver repeatedly. Though he made a quick work of two of his opponents, he too was disabled by a shot to the right hand.

The quick response made by the reserves delayed the advance of the 21st New York long enough to allow most of the trapped members of the 18th Virginia to escape from the fenced-in confines of Bonnie Doon. Their intervention also allowed the 23rd Virginia Cavalry time to add their weight to the Confederate assault. These men came charging down the road and joined in the resistance offered by the boys and old men.

The 18th Virginia Cavalrymen, able to extricate themselves safely, were able to retreat and reform. The timely arrival of the reinforcements had, however, saved the Virginians from capture or death. The intervention of the Boy Company and the Old Men had saved the day for Imboden and the Virginia cavalrymen.

The Confederate cavalry force was finally obligated to retreat to a point where they could reform once again. This they would do time and time again. Imboden’s cavalry would “deploy at every hill” leading to the defensive position chosen by General William Jones at Piedmont.

Chrisman’s Boy Company had suffered heavily in the fighting. Less than one month before they had numbered eighty souls. Major Chrisman would indicate he had brought forty-five of the sixteen and seventeen-year-olds into the fight at Bonnie Doon. He later noted that they had “made a desperate stand,” along the East Road, outnumbered, and fighting against the skilled veterans of the 21st New York Cavalry. In this brief episode they had lost thirty members of their company; two thirds of their numbers.

Remarkably, John and William Hooke survived the encounter. Both would outlast the war and return home a year later. John did not remain in Cross Keys, however, but decided to head west to California. He would marry Emma Van Lear and raise two children to adulthood there. He would die at his home in Pomona California in 1923. His dad would pass away shortly after the war and is buried in the Cross Keys Cemetery.

Later that day a major battle would take place at the village of Piedmont with General William “Grumble” Jones commanding. Outnumbered, the battle would go badly for the Confederates. In the intense fighting General Jones was killed and the Confederates routed. Before the battle General Imboden had assigned a 4 foot 10-inch-tall private, named Joseph Altaffer, to Jones as a courier. He was the shortest member of the Boy Company. He was at General Jones’s side when he was struck in the head and killed by a Union bullet. Altaffer would be one of just two of the original members of the Boy Company who would live to surrender at Appomattox Court House. Though the bravery of the boys would, deservedly, “spread through the Valley,” most would not survive the war. Their courage and sacrifice was absolute.

The neighing troop, the flashing blade

The Bugles stirring blast

The Charge, the dreadful cannonade

The din and shout are past.

Anonymous

Sources:

Beach, William H. The First New York Lincoln Cavalry: From April 19, 1861 to July 7, 1865. The Lincoln Cavalry Association. New York. 1902.

Bonnell, John C. Jr. Sabres in the Shenandoah: The 21st New York Cavalry, 1863-1866. Burd Street Press. Shippensburg, Pa. 1996.

Heatwole, John L. “Remember Me is All I ask:” Chrisman’s Boy Company. Mountain Valley Publishing. Bridgewater, Va. 2000.

War of the Rebellion, Official Records. Union and Confederate Armies. Series I. Volume XXXVII.

Hi Pete –

Thank you for an extremely interesting article. I could see myself in this battle; great narrative. I want to see Bonnie Doon someday, if it still exists.

Stay healthy, and best wishes to your family

Otis Fox (123d Kentucky Regt, Orphan Brigade, Army of Tennessee)

LikeLike

It very much exists. The landowners are good friends of mine, and fellow members of our local fixhunt club. This farm is a lovely place to ride horses and we frequently view beautiful healthy foxes. “Tally ho!”

LikeLike