I remember, when as a young adult back in Maine, spending some quality time one evening watching a World War II movie with my dad. The film was called Patton. The motion picture had come out in 1970 so I would have been a senior in high school at the time. After the film was over, I thought this might be an appropriate time for me to quiz him once again regarding his wartime experiences. He had always been very evasive on the subject, stating he had few fond memories from that time. As a young boy I had often interrogated him on the subject. This time I thought he might feel more comfortable addressing the subject. He was not.

My Dad had fought as a private first class with the 28th Infantry Division during the war. The patch they wore on their shoulder was a red keystone symbolizing the State of Pennsylvania. The unit had been given the nickname “Bloody Bucket” division by German forces due to the shape and color of its keystone insignia. In little more than a month after landing at the Normandy beachhead, as part of the Allied invasion of Normandy, the men of the 28th had entered Paris and were given the honor of marching down the Champs-Elysées on August 29, 1944. My dad had mentioned this honor several times.

28th Infantry Division Patch

The 28th suffered extremely heavy casualties that autumn during the costly Battle of the Hürtgen Forest which took place between September 19 and December 16. The campaign was the longest continuous battle the U.S. Army fought during World War II. My dad once told me he had frozen his feet on a cold December night in that woodland. He said most of the men in his company had never been fitted with the proper winter footwear.

Sometimes he would talk about how cold it had been during “the Bulge.” He once confided to me that on one of those freezing nights, during an artillery bombardment, he had been compelled to leave his foxhole to relieve himself. In his absence his bunker received a direct hit from German artillery fire killing every one of his comrades hunkered there. It always brought tears to his eyes when he talked about it. I asked him once if he would like to attend one of the 28th Infantry Division’s reunions. He told me all the people he would like to see again had been killed in that foxhole and buried in Liege, Belgium.

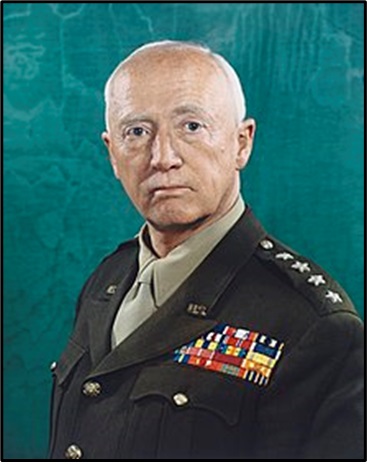

Coincidentally, one of the most memorable events about which he often spoke was a close encounter he had with a high-ranking army officer. He said he was ambling down a street one cold winter morning and was attempting to pass by a man who was approaching him dressed in what appeared to be a private’s uniform. The soldier suddenly grabbed my dad by the arm, spun him around, and demanded that he salute him. He interrogated my father as to why he had not done so. He warned him he could be court martialed for not saluting a superior officer. The officer addressing him was “Old Blood and Guts” himself, George S. Patton the III. Fortunately, my dad was never punished or court martialed for his transgression. He did say the incident “scared the bejesus out of him” though. My dad passed away in 2004 and the story of the George Patton encounter would be the one war story he related most often.

General George S. Patton III of WWII Fame.

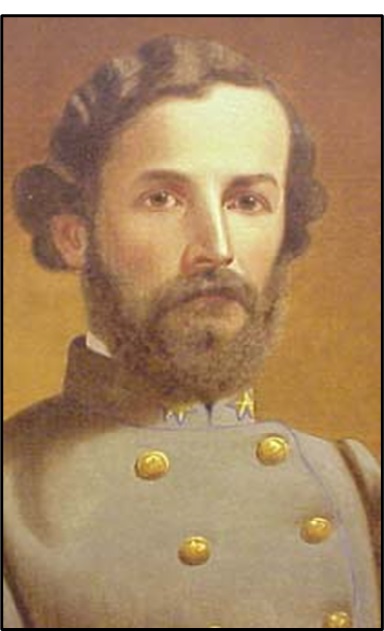

My narrative, though, is not about George S. Patton III, or my father, but it is about George S. Patton Senior, George’s grandfather. George Sr. was born in Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1833. He graduated from Virginia Military Institute in 1852 second in his class. Patton would go on to teach school in Richmond while at the same time studying law. He would resign his position in the fall of 1855 after being admitted to the Richmond Bar Association. In November of that same year, he and Susan Thornton Glassell of Alabama would be married. “On their wedding night the couple headed for Charleston, Kanawha County, in what is now West Virginia. Patton had been offered a partnership in a small law firm.”

Colonel George Smith Patton, Sr.

In 1856 George organized a militia company called the Kanawha Minutemen, later the Kanawha Riflemen. The company had a strength of from 75 to 100 men, of whom 20 were lawyers. “The company was comprised of the Kanawha Valley’s social elite. They performed at public functions throughout the state, earning a reputation that they could perhaps dance better than they could fight.” Such thoughts were put to rest in 1861 when the Riflemen became the foundation of the 1st Kanawha Regiment, which would later evolve into the 22nd Virginia Infantry.

When the Civil War broke out Patton enlisted on May 8, 1861, becoming the captain of Company H of the 22nd Virginia Volunteer Infantry. Patton’s first experience with combat came on July 17, 1861, at Scary Creek, just a few miles outside of his hometown of Charleston. Recently commissioned as a lieutenant colonel, Patton commanded some eight hundred and fifty men who were part of a force under the direction of Brigadier General Henry Wise. This small Confederate army had been tasked with resisting a Union push up the Kanawha Valley. The Federals were part of Brigadier General George McClellan’s drive into western Virginia from Ohio. Late in the battle, while trying to rally routing troops, Patton was struck by a minie ball in the right shoulder. The impact of the bullet shattered the bone and threw him from his horse.

Patton was transported to the rear and was informed that his arm needed to be amputated. Patton refused to have the limb removed. To emphasize his determination to keep the extremity he is reputed to have pulled a pistol and threatened his caretakers. Patton kept his arm, but never regained full use of it. The Confederates did not win the battle and were forced to retreat from the Kanawha Valley. Unable to be moved because of his wound, Patton was left behind and captured. A few weeks later he was paroled and went home to recuperate. He would spend the next eight months recovering from his wound.

Returning to his regiment Patton saw action again on May 10, 1862, when he led the 22nd Virginia in an attack against a Union regiment at Giles Court House in Virginia. Brigadier General Henry Heth led a small brigade, including the 22nd and 45th Virginia, against the 23rd Ohio, now under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes. According to the May 20, 1862, edition of the Richmond Dispatch “the command of General Henry Heth was informed that they would meet the enemy on the following morning, and preparations were at once made for an advance. At daylight the next morning the column reached the vicinity of Pearisburg, the enemy’s pickets were driven in, and a general firing commenced, the 45th on the right, and the 22d on the left. The fight lasted one hour and thirty minutes, when the enemy were driven from their position, through the town of Pearisburg and down New river below the Narrows. Our forces behaved with great gallantry, and kept up the pursuit as far as the Narrows. The loss on our side was one killed and seven or eight wounded.” Among the injured was George Patton.

Colonel Patton had been wounded once again. This time he had been shot in the abdomen. “Patton was laid against a nearby tree and, fearing that he was dying, he began writing a farewell note to his wife. General Wharton, his brigade commander, rode up and asked him how he was doing. George answered that he believed the wound was fatal. According to Patton’s son, George William, Gen. Wharton dismounted and asked if he could examine the wound. He stuck his unwashed finger into it and exclaimed, ‘What is this?’ as his finger hit something hard. He then fished around and pulled out a ten dollar gold piece. The bullet struck this and had driven it into his flesh and glanced off.” Patton would survive his injury.

Patton’s finest hour, however, probably came at the Battle of New Market. The 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment was part of a small army under the command of Major General John C. Breckinridge. The army had been quickly created to resist a Union thrust under Major General Franz Sigel who was pushing up the Shenandoah Valley. The Confederates were so greatly outnumbered they had to call upon 247 cadets from the Virginia Military Institute to serve as reinforcements. One of the cadets who would fight with the Corps of Cadets was Patton’s youngest brother, William Mercer Patton.

The fight took place on May 15, 1864. In the ensuing battle the Confederates made a stand against superior numbers of Union troops. During the latter stage of the battle, Patton was commanding the First Brigade in place of the sickly Echols. Patton’s two regiments numbered about a thousand men. He was defending the right of the line against a Union cavalry charge which was attempting to break through and outflank the Confederate line. When the cavalry charge broke through, Patton maneuvered the 22nd Virginia and the 23rd Virginia to either side of the gap in the line creating a deadly crossfire. The cavalry charge led by Major General Julius Stahel ran straight into ten pieces of artillery including six guns from Chapman’s Battery, a section of artillery manned by VMI cadets, and two guns from McClanahan’ battery under Lieutenant Carter Berkeley. The combined Confederate firepower devastated the Union cavalrymen, forcing them to route to the rear. Many troopers were killed, wounded, or captured.

On September 19, 1864, at the Third Battle of Winchester, Colonel Patton again found himself in command of Echols’ brigade. When the engagement opened, Patton’s brigade was first tasked with supporting Confederate cavalry along the Martinsburg Pike North of Winchester near Stephenson’s Depot. As the battle expanded in his rear Patton was gradually forced to move his brigade south toward Winchester and to the east side of the Pike. By late afternoon Patton’s brigade anchored the Confederate left flank near the Hackwood Plantation.

Patton’s Retreat from Hackwood at the 3rd Battle of Winchester. (Map provided by SVBF, and made by H. Jesperson)

Around 3 pm, as Major General John Gordon’s Division was being pushed back, Patton’s three regiments were making a stand on the left of the line against a determined attack by Colonel Isaac Duval’s Division. On his right, Gordon’s division began to fall back under pressure from Colonel George Well’s and Colonel Thomas Harris’ Infantry Brigades and from the 1st New York Dragoons and the 9th New York Cavalry on their left. Cut off and nearly surrounded Patton was forced to retreat. It was during this retreat and attempted rally that Patton was struck in the right leg by a jagged piece of iron from a bursting artillery shell.

Robert H. Patton, in his book on the Patton family, described George Paton’s wounding: “He was standing in his stirrups on a Winchester Street when an artillery shell exploded nearby and sent an iron fragment into his right hip. He’d been trying to rally his men, who were in full retreat before onrushing Yankee cavalry….” He was taken to a nearby house and later captured.

Philip Williams House where George Patton Died from His Wounds.

George S. Patton II and George S. Patton III at the grave of George S. Patton Sr. who was killed during the Third Battle of Winchester.

Patton twisted in agony until Union soldiers captured him and took him to the home of Philip Williams on Piccadilly Street. The amputation of his right leg was recommended by Union physicians, but Patton refused as he had once before when wounded in the arm. Within a few days gangrene set in and on September 25, 1864, he died of his wound. His body was interred in the Stonewall Cemetery, in Winchester, not far from where his wound had been inflicted. He was buried next to his brother Colonel Waller Tazewell Patton of the 7th Virginia Infantry who had been mortally wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg during Pickett’s Charge.

Neither George Patton senior or George Patton junior would gain the same notoriety as the third descendant in the Patton line for commanding a tank brigade in World War I or for commanding the Third Army in World War II. For the war in which George Senior fought he was the man the younger Patton regarded passionately as the quintessential soldier, one who had demonstrated extraordinary courage in battle and had met his demise while leading his troops in a desperate fight. His grandson would attempt to do the same during a German counteroffensive in the Ardennes Forest in December of 1944. Now you know the genesis of my father’s respect for a man who once threatened to court martial him for passing him by.

Besides George, six other Patton boys would go off to fight for the Confederacy.

- John Mercer (1826-1898) would become the commander of the 21st Virginia, but had to resign in August 1862 owing to poor health.

- Isaac William (1826-1890), would lead a Louisiana regiment and be captured at Vicksburg.

- William Tazewell (1835-1863), would command the 7th Virginia and be killed at Gettysburg during Pickett’s Charge.

- Hugh Mercer (1841-1905) became an officer in his brother’s 7th Virginia Infantry.

- James French (1843-1882) became an officer with George in the 22nd Virginia.

- William Macfarland (1845-1905) who was a cadet at VMI, would take part in the battle of New Market.

Sources:

Patchan, Scott C. Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, Nebraska. 2007.

Patchan, Scott C. The Last Battle of Winchester: Phil Sheridan, Jubal Early, and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, August 7 to September 19, 1864. Savas Beatie. El Dorado, California. 2013.

Richmond Dispatch. May 20, 1862

SVBF, Shenandoah Valley Battlefield’s Foundation.

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/general-george-s-patton-sr-civil-war-veteran/

Yes, but striking two different enlisted men was super not cool. The WW II vets I knew liked Patton, but with strong reservations. Having spent 28 years in the Army,. I appreciate better what a severe violation of a certain ethos that was.

Tom

LikeLike

This is an excellent post! Sent from my iPad

LikeLike