At the time of the American Civil War Canada was comprised of several British colonies. There was Canada West and Canada East or what is now Ontario and Quebec. There was also the Maritime Colonies which included Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. The Country of Canada as we know it today would not be created until 1867, two years after the American Civil War.

Britain, and her colonies, quicky declared themselves neutral when the Civil War broke out, announcing it would support neither the Union nor the Confederacy. As a result, Canada and the Maritimes were officially nonaligned. Still, most Canadians were largely opposed to slavery, and as we know they had long been the terminus of the Underground Railroad. Close economic and cultural ties across the border, though, encouraged Canadian sympathy towards the Union cause. Record keeping was rather slapdash back then, so exact numbers are impossible to determine, but it is estimated that between 35,000 and 50,000 Canadians fought in the war. Most fought for the North but several hundred, especially many of those that lived in the Maritimes, fought for the Confederacy. About twenty-five hundreds of these Canadians were black. Countless of these were escaped slaves.

Lots of those that volunteered were already working in the United States when the war began and countless numbers of them joined with local regiments. Others left Canada to enlist. “Some were tricked, bribed and even kidnapped by ruthless American recruiters, called crimpers.” Canadian and Maritime soldiers and sailors fought in nearly every battle of the American Civil War. By the end of the war, many had become officers and twenty-nine of them would earn the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Edward Edwin Dodds, for example, was born in Chesire, England in 1845. His family emigrated to Port Hope, Canada West, (Ontario) in 1859. At the age of 18, Dodds took a steamer across Lake Ontario to Rochester, New York and enlisted for a three-year term of military service. He enrolled on July 31, 1863, and was officially mustered in on August 28 as a private in Company C of the 21st New York Volunteer Cavalry (also known as the Griswold Light Cavalry).

The regiment served in the Department of Washington until January 1864, when it was assigned to Brigadier General George Crook’s Army of West Virginia. His regiment was designated as part of Colonel Andrew McReynolds’ 1st Brigade in Major General Julius Stahel’s First Cavalry Division. Colonel William B. Tibbitts was their regimental commander.

Post War Photo of Sergeant Edward Edwin Dodds

Dodds was promoted to the rank of sergeant on May 1, 1864, and in less than a week he found himself attached to General Franz Sigel’s command advancing up the Shenandoah Valley. On May 15 the leading elements of this Union Army, including the 21st New York, would begin to arrive at New Market. Sigel’s Army of West Virginia, though, was strung out along the Valley Pike all the way from Woodstock to New Market.

The Battle of New Market began midmorning with General John Breckinridge’s Confederate forces and Colonel Augustus Moor’s Union Brigade engaging each other on the west side of town. As the day progressed General Sigel arrived and began to push slowly reinforcements into the battle as they arrived. As the fight escalated the Union Army was driven steadily back. General Breckinridge reluctantly realized that if he was to win the battle, he would need to call up all his reserves, including the Cadets from the Virginia Military Institute. With these young boys thrown into the fight it began to look like the Confederates would carry the day.

Out of desperation, General Stahel ordered his entire Union cavalry division to form up on the east side of the Valley Pike. Colonel William Tibbitts, who had recently been promoted to command of the 1st Brigade, was to lead the charge. The 14th Pennsylvania and the 21st New York were to be at the head of the column. Sergeant Dodds was about to see the elephant for the first time.

As the cavalry attack pushed forward a hole opened in the rebel line and the cavalrymen plunged in. Musket fire was directed at them on the right by the 22nd Virginia and on the left by the 23rd Virginia Battalion. Artillery fire from three batteries raked them from the front. One of the federal cavalrymen remembered that they “mowed us down like grass.”

The Union cavalry attack was quickly repulsed with significant casualties. Sigel’s army was completely routed from the field. The cavalrymen of the 21st New York joined in the general retreat from the battlefield. The regiment, itself, was fortunate as they had just three troopers killed, twelve wounded, and three captured in the desperate assault. Sergeant Dodds had escaped completely unscathed.

The 21st New York led the retreat down the valley. About 3:00 A.M on May 16 the regiment arrived at Strasburg and setup camp. Colonel Tibbitts’ Brigade was in poor condition. They were short on arms, ammunition, and food. Though the men in the regiment considered the recent battle hard fought commanding General Ulysses S. Grant did not see it that way. Disappointed and angry with the outcome of the fight he quickly ordered General Sigel to be replaced.

Sigel would retreat his army to Cedar Creek and establish his headquarters at Belle Grove Plantation. Late on May 21, Major General David Hunter arrived at Middletown and relieved Sigel of his command. Hunter informed him that he had been ordered to take charge of the Union Army’s Reserve Division at Martinsburg.

General Hunter had been ordered by General Grant to move immediately to Staunton and join up with Generals George Crook and William Averell. If possible, he was to advance on Charlottesville or Lynchburg destroying everything of military value on his way especially the railroad. Hunter began his movement on May 25. He ordered his men to pack eight days rations and one hundred rounds of ammunition. Any additional food was to be foraged from the residents of the Shenandoah Valley.

Captain James Graham of Company H was detached with the 21st New York’s small rear echelon unit prior to General David Hunters departure from Cedar Creek. Edward Dodds would be assigned to this unit. The main body of the regiment would remain with General Hunter’s command. The small detail was to be dispatched to Camp Stoneman, which was a military post named after General George Stoneman, a prominent Union cavalry commander. The base was located near Washington D.C. and served as a staging area for cavalry troops. Graham’s job was to receive the new recruits that had arrived from Troy, and other New York state recruiters, and shape them into cavalrymen. On June 17, Captain Graham along with the small detachment of New York troopers brought fifteen hundred cavalry reinforcements from Camp Stoneman to the Shenandoah Valley.

While all this was transpiring General Hunter would fight a costly but successful battle at Piedmont. He would continue on to Staunton and Lexington burning key infrastructure as he went. In his assault on Lynchburg, he ran up against a determined foe in the form of General Jubal Early’s Second Corps. Following several clashes with Confederate troops Hunter rashly decided to withdraw. While the rest of Hunter’s men were making their way back to Martinsburg by way of Parkersburg and Charleston, West Virginia, Jubal Early’s Army was making its way down the valley on their way to Washington D.C.

The main body of the 21st New York would not arrive back in Martinsburg by train until July 15. In the waning days of June, however, the so-called Reserve Division, which included the detachment from the 21st New York Cavalry saw action several times from their base camp at Bunker Hill. The troops stationed there were commanded by Union General Franz Sigel.

In the early morning of July 3rd, for example, a detachment of Colonel Harry Gilmore’s cavalry numbering about one hundred men initiated a foray toward Bunker Hill along the Martinsburg Pike. A small party of the 21st New York had been designated to guard the ford at Mill Creek. Gilmore launched a surprise attack out of the early morning fog on the New York boys. The detail was quickly routed and forced to retreat to Buckletown about five miles south of Martinsburg. Following along on their heels Gilmore attempted a second charge. The regiment was ready for him this time. The New Yorkers fired several volleys into the Confederate cavalry as they advanced and then launched their own counterattack sending Gilmore’s men reeling up the Martinsburg Pike.

Under mounting pressure from Jubal Early’s Army Sigel withdrew his troops from Martinsburg to Maryland Heights attempting to defend the town from an assault by Confederate forces. During their retreat the 21st New York ran up against the Confederate rear guard outside of Martinsburg. The unit made two desperate charges against rebel pickets and were finally able to break through and cross the Potomac River. The cavalry regiment continued on to Harpers Ferry and Sandy Point where they were shielded by the guns on Maryland Heights.

Early sent troops to seize Bolivar Heights and Harpers Ferry. Once again, as in previous attempts, Federal forces offered little resistance, instead retreating to the protection of the siege cannons on Maryland Heights. This defense, however, delayed Early for two days and undoubtedly helped save Washington. Sergeant Edward Dodds, however, was wounded in the fighting here.

The 21st New York was not directly involved in combat at the Battle of Monocacy. The regiment did engage with Early’s rear guard on the Monocacy Battlefield after the fighting had ended, however, chasing it for four or five miles. When the unit ran up against concentrated artillery fire, they prudently retreated to the Monocacy River. Losses amounted to one killed, one wounded, and one captured.

Dodds recovered from his wound, and his rear echelon detachment rejoined the main body of the 21st New York shortly after their arrival at Martinsburg on July 15. Within hours they were dispatched to Harpers Ferry to join in the effort to intercept Jubal Early’s Army on its retreat from Washington. When news reached General Duffié, who now commanded the cavalry division, that Early’s wagon train was unprotected and heading toward Ashby’s Gap he dispatched his first brigade commander, Colonel William Tibbets, to intercept it. At this moment the brigade consisted of the 21st New York Cavalry, a small number of cavalrymen from the 2nd Maryland, as well as a section of artillery from Battery B of the 1st West Virginia Artillery. Total strength was about 270 men.

Colonel Tibbitts spotted the wagon train at about four in the afternoon and set up an ambush to try to capture or destroy the wagons. The 21st New York came swooping down on the procession while the 2nd Maryland, outfitted with repeating carbines, attacked from the rear. Confederate forces were soon able to mount a counterattack forcing the 21st New York to retreat. Still, nearly 40 wagons were captured, while many others were destroyed. Fifty or more prisoners were taken. The regiment had one killed, five wounded, and twelve captured.

About 9:00 A.M on the morning of July 17, General Duffié was ordered to escort James Mulligan’s Infantry Brigade from Harpers Ferry to Snicker’s Gap in the Blue Ridge. The detail reached Snickersville at about 1:30 in the afternoon. After a short rest they descended the mountain to the west bank of the Shenandoah River where they immediately came under fire from Confederate infantry dug in on the opposite shore.

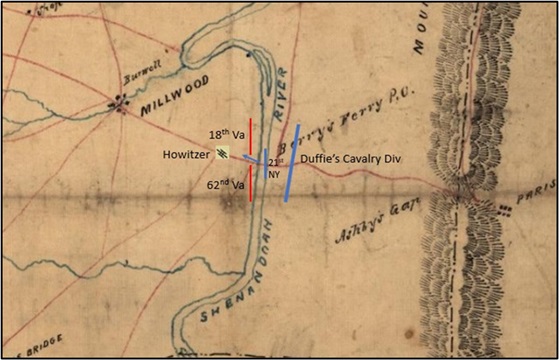

Battle at Castleman’s Ferry July 17-18, 1864 (Map Modified by the Author from Hotchkiss Map located in the Library of Congress)

Mulligan decided he would try to force his way across the river at the ford. The river was waist deep and fast moving “with a bottom that was rocky, slippery, and uneven.” A charge on the Confederate forces on the opposite shore was contemplated but was quickly reconsidered due to heavy the heavy musket and artillery fire. About 6:00 P.M. Tibbitts became discouraged with the standoff but did not order his men to retreat back up through the gap until dark. He left a small picket line behind to secure the position on the west bank.

Later that evening when things had quieted down Tibbetts began to think Gordon might have withdrawn his forces on the other side of the river. At about midnight the order was given to the 22nd Pennsylvania to attempt a crossing. As horses began to wade into the river the suddenly came alive with bright flashes of fire. Gordon’s men had not gone anywhere. The attack was quickly called off.

On the morning of July 18, General George Crook arrived at the gap and ordered another crossing to be attempted. Colonel Duffié directed the 22nd Pennsylvania to make a coordinated attack with seventy-five cavalrymen. They were to attack in three columns, one hundred yards apart, each containing twenty-five men. The assault immediately came under heavy fire from sharpshooters on the far bank. Convinced that the opposing shore was securely manned, the attackers were called back.

Casualties at Castleman’s Ferry were light. Seven members of the 21st New York were killed and two were captured. The failed crossings convinced General Crook, however, that it would be better to force a crossing downstream and launch an attack on the Confederate left flank. This decision would culminate in Union Army’s defeat at the Battle of Cool Spring.

Following the two failed attempts to force a crossing at the ford General George Crook ordered Duffié to ride with his fellow cavalrymen to Ashby’s Gap, cross the river, and threaten Early’s supply train. Shortly after noon Duffié’s Cavalry Division was dispatched from Castleman’s Ferry. By 7:00 P.M. that evening, the 21st New York had reached the town of Paris, Virginia, adjacent to the gap. They bivouacked here for the night.

At 7:00 A.M. the following morning Duffié’s Division crossed through the gap to Berry’s Ferry on the Shenandoah River. Lieutenant Colonel Gabriel Middleton’s Brigade led the push across the river. John Imboden’s Brigade, however, was concealed on the opposite bank and when the Federals were part way across the river, they opened up on them. Elements of the 1st New York and 20th Pennsylvania Cavalry continued their advance under heavy musketry fire. Though they experienced some initial success they were eventually forced to retire back across the river.

Colonel Tibbets deployed some of his dismounted cavalrymen along the eastern riverbank and instructed them to maintain their fire on the opposite shore. About four in the afternoon Tibbitts was called to Duffié’s command post. Duffié ordered Tibbitts to force a crossing of the river. Tibbitts voiced the opinion “the stream could not be crossed owing to the enemy and their location.” Duffié refused to listen and Tibbitts was left with no choice but to comply with the order.

Colonel Tibbitts chose the 21st New York to make the crossing. He ordered Colonel Charles Fitzsimmons, who commanded the New Yorkers, to commence a mounted charge across the Shenandoah River and secure the opposite bank. The 1st New York was ordered to provide support. There was to be a short artillery bombardment by Keeper’s Battery and then the New Yorkers were to sound the charge.

Map Adapted from Jedediah Hotchkiss Map. (Library of Congress)

When the artillery barrage was completed the 21st New York, with fewer than 300 men, dashed across the river to the opposite bank. Several of the men broke through the Confederate line and drove on to within a few yards of the howitzer on the hill. The volume of fire from the Confederates was considerable. The 18th Virginia fired at the attackers on their right and the 62nd Virginia charged them on their left. Unsupported the 21st New York was forced to retreat. Colonel Fitzsimmons was shot in the wrist and at least eighty of the regiment’s officers and men were lost before the unit could make it back to safety on the eastern shore.

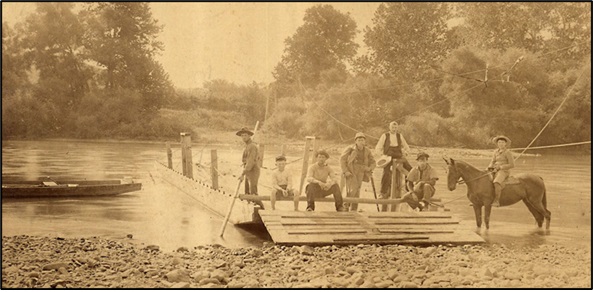

Late 1800’s Photo of Berry’s Ferry at Ashby’s Gap. The 21st New York Cavalry Attack Would Have Come from the Opposite Shore (Clark County Historical Society)

Following is an account published in the Rochester, New York, Democrat and Chronicle on June 13, 1896. “The 21st N. Y. Cavalry crossed the river at Ashbey’s [sic] Gap, in their advance, and very soon afterwards came upon the enemy in force, in the woods, who opened a sharp fire upon them. They were not nearly sufficient in number to withstand the attack and a retreat was ordered. At this time the captain of C Company (Lewis Truesdell) was severely wounded and his horse killed, and the captain found himself unable to extricate himself from his fallen horse. With the bullets flying around him, Sergeant Dodds dismounted, disengaged his captain and assisted him onto his own horse, which he also remounted. The enemy had meanwhile got around to the rear, and when our hero arrived at the ford he found it already occupied. Undismayed by this circumstance he turned his horse along the bank until he came to a favorable spot, when he leaped his horse into the river and swam across under fire, reaching the union lines in safety with his captain, who afterwards recovered and is among those who testified to the war department as to the incident.”

Casualties in the action were substantial. Among the wounded was Captain Lewis Truesdell whom Sergeant Dodds had saved from capture. Also on the wounded list was Edward Dodds himself. The wounds must have been superficial as both men were back with their regiment on July 24 in the events leading up to and including the Second Battle of Kernstown. As a matter of fact, Captain Truesdell was wounded there once again when a bullet glanced off another cavalryman’s saber and struck him in the shoulder.

In the month-long period following the 2nd Battle of Kernstown the 21st New York spent its time refitting and reacting to rumors of Confederate incursions into West Virginia and Pennsylvania following the burning of Chambersburg. Dodds and his regiment were dispatched to guard various fords along the Potomac River. General Philip Sheridan assumed overall command of the Middle Military District on August 7 at which time the New Yorkers were ordered to march to Harpers Ferry to join with the rest of the army.

Action at Charlestown August 21, 1864 (Author Adapted the Hotchkiss Map Located at the LOC)

On the morning of August 24, Duffié’s Division was positioned west of Charles Town on the Leetown-Charles Town Road. During the fighting here Tibbet’s Brigade rode into an ambush. Gilmore’s troopers were concealed in a wood and fired upon them as they attempted to pass. Most of the brigade’s casualties were suffered by the 12th Pennsylvania Cavalry. One of the members of the 21st New York who was wounded, though, was Sergeant Edward Dodds. He was injured, apparently, while firing from a prone position. A bullet struck Dodds in the face, glanced off his cheekbone, and ricocheted into his right arm.

The wound was serious and required the amputation of Dodds’ right limb. If you view the post war photo of him above only his left arm is exposed. The injury necessitated some extended recovery time in the hospital. Instead of receiving a discharge, though, six weeks after losing his arm Sergeant Dodds asked he be allowed to rejoin his command. Dodds reported back to the regiment for duty at Pleasant Mountain Remount Camp, which was situated between Elk Mountain and South Mountain in Maryland. He remained on duty there as a clerk with this detail until the close of the war, when he mustered out with his comrades. Dodds was, in fact, discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability on July 29, 1865, at Alexandria, Virginia “by reason loss of right arm and other wounds received.”

For his outstanding bravery and courage at the Battle of Ashby’s Gap Sergeant Dodds was awarded the Medal of Honor on June 11, 1896. Though he is certainly not the only man to earn the distinction while serving in the Union Army he is the only Canadian to do so while fighting in the Shenandoah Valley. His citation reads: “While engaged with Confederate forces at Ashbys Gap, Virginia, on July 19, 1864, a captain of the 21st New York Cavalry fell wounded on the battlefield and lay at the mercy of the enemy. Without regard for his own safety, Sergeant Edward Dodds braved the fusillade to go to his captain’s side and carry him to a place of safety.”

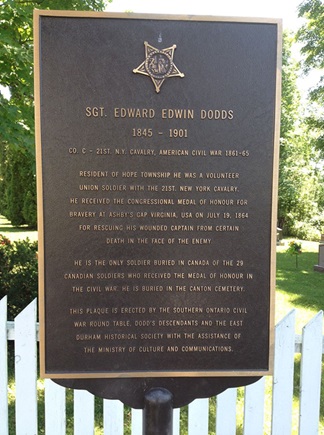

Marker Outside the Canton Cemetery in Ontario Commemorating Edward Edwin Dodds receipt of the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Following his discharge from the U.S. Army and 21st New York Volunteers, Edward Dodds opted to remain in the United States. Settling in Rochester, New York, he secured employment as a reporter with Rochester’s newspaper, the Democrat and Chronicle. During the 1870s he chose to return home to Canada where in 1877 he became the Town Clerk of Hope Township in Northumberland County, Ontario. From October 13, 1892, until at least early 1896, he served as the U.S. Consular Agent for Port Hope’s Peterborough office. Dodds died on January 12, 1901, and was laid to rest where his parents had been interred at the Canton Cemetery in Canton, Ontario.

Twenty-nine Canadians received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the American Civil War. At least nine of these recipients are buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Again, it should be noted only one of these Medal of Honor recipients, Edward Dodds, is buried in Canada.

Only four Canadians were awarded the Medal of Honor after 1900. One of those was Douglas Munro who was born in Vancouver, Canada. He is the only person from either country to have received the medal for actions performed during their service in the United States Coast Guard.

Medal of Honor Citations for individuals born in other countries other than the U. S. during the Civil War:

Australia 1, Austria 1, Chile 1, Czeck Republic 1, Denmark 2, England 46, France 12, Germany 45, Hungary 1, India 1, Ireland 102, Italy 2, Malta 1, Netherlands 2, Norway 6, Poland 1, Russia 1, Scotland 18, Spain 2, Sweden 5, Switzerland 1, and Wales 6.

Of the 1,522 Medals of Honor issued for service in the Civil War, including Canada, 287 (19%) were awarded to foreign born soldiers.

More to come.

Sources

Bonnell, John C. Sabres in the Shenandoah: The 21st New York Cavalry, 1863-1866. Burd Street Press. Shippensburg, Pa. 1996.

Knight, Charlie. Valley Thunder: The Battle of New Market and the opening of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign May 1864. Savas Beatie. New York, N. Y. 2010.

Noyalas, Jonathan. The Blood-Tinted Waters of the Shenandoah: The 1864 Valley Campaign’s Battle of Cool Spring, July 17-18, 1864. Savis Beatie LLC. El Dorado, Ca. 2024.

Patchan, Scott. Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, Nebraska. 2007.