Sandy Pendleton recorded that the combat at First Kernstown “was a harder fight than Manassas.” In two hours of fighting a quarter of Stonewall Jackson’s army became casualties in one form of another. In addition to the two hundred and sixty-three that were captured, and the eighty were killed, three hundred and seventy-five were wounded. Many of the injured would have been left behind as the Confederates were forced to relinquish the field. It would have been the walking wounded, and those receiving assistance from comrades, that would have been able to escape the battlefield.

In his book, Stonewall in the Valley, Robert Tanner wrote that “by dawn on March 24, after all Confederate wounded were on their way to the rear” the Valley Army started their retrograde movement. The wounded were, quite naturally, given priority and were already proceeding in the direction of the nearest aid station. This was as it should be.

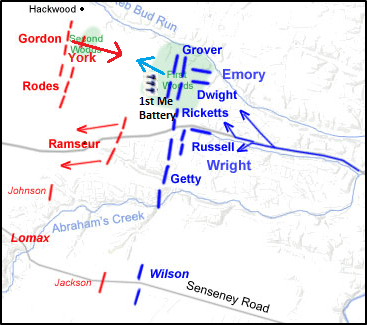

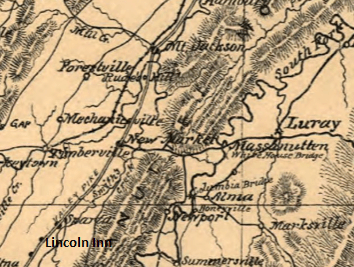

Fortunately for Stonewall Jackson, the wounded had the advantage of walking, or being transported along the best road in the Shenandoah Valley. Further, the Valley Pike passed right by the front doorstep of the only Confederate military hospital in the lower Shenandoah Valley. In addition to the best road, Mount Jackson also served as the western terminus of the Manassas Gap Railroad. As long as the rail line or the Valley Pike were free from Union occupation, it was a logical place to build a hospital. Sick and wounded soldiers could easily be directed toward the facility by foot, by ambulance, or by rail.

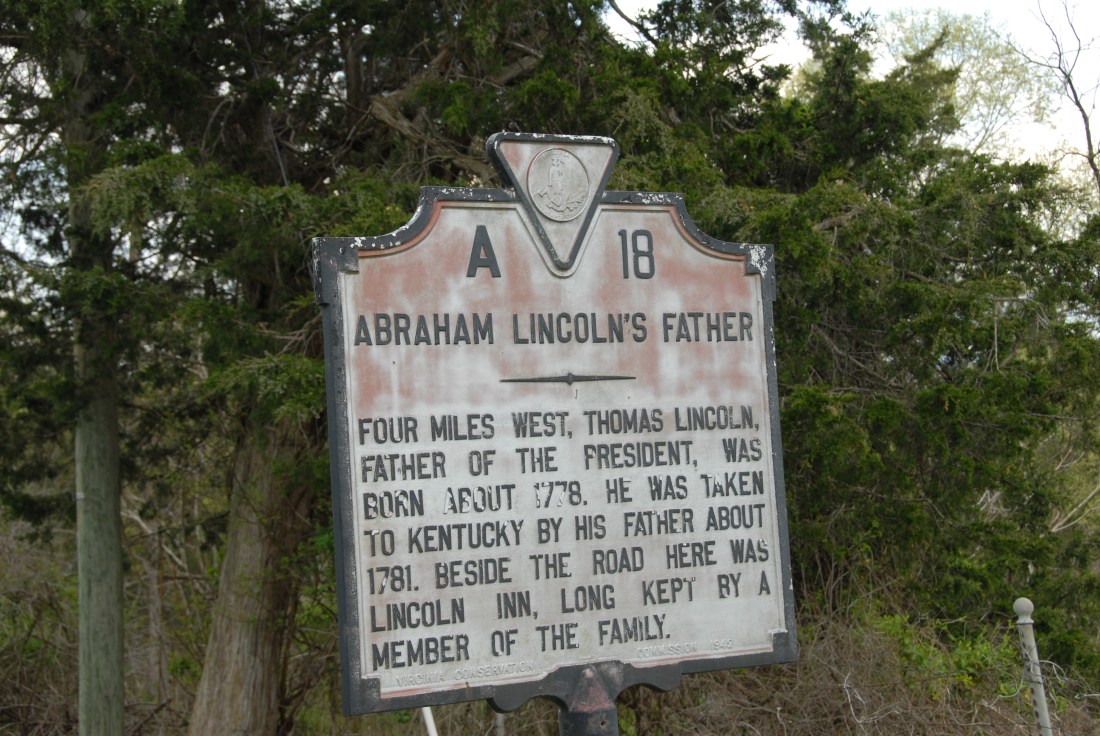

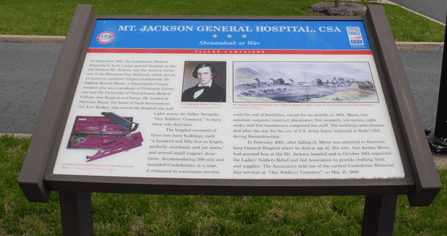

Sign Marking the Location of the Confederate Hospital at Mount Jackson

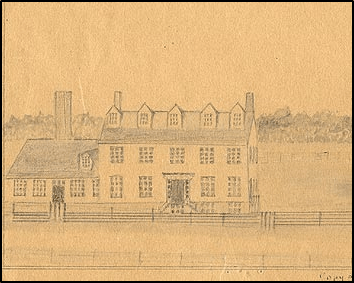

In September 1861, shortly after the First Battle of Manassas, the Confederate Medical Department had ordered a hospital be built in the town of Mount Jackson. That same month, Doctor Andrew Russell Meem, a resident of the town, was contracted to design and construct an infirmary there. The facility would consist of “three, two story buildings which were one hundred and fifty feet in length.”

The hospital was designed to accommodate some five hundred patients. The staff would include “Dr. Meem, two assistant surgeons, five stewards, ten nurses, eight cooks, and five laundry workers.” Dr. Meem, himself, was a well-respected area resident who was a graduate of both Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania Medical College. The doctor had been the head surgeon for the town of Mount Jackson before the war.

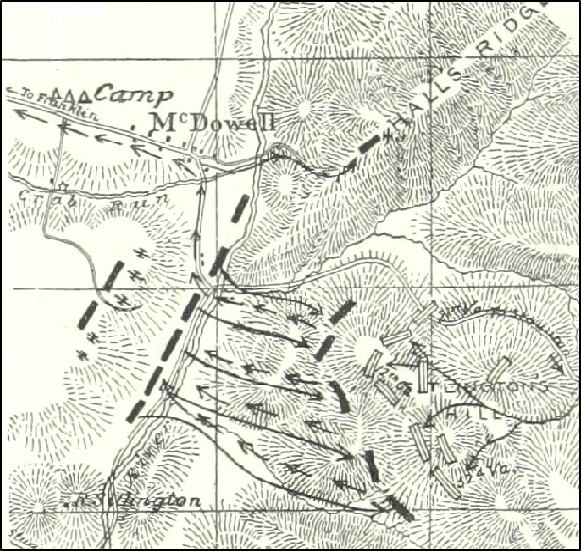

Plaque Showing the Design of the Mount Jackson Hospital

The parcel the hospital was built upon was donated by another Mount Jackson native, Colonel Levi Rinker. The building materials, though, were contributed by the Meem’s family. The Meem’s resided on a twenty-five-hundred-acre plantation they called Mt Airy. The residence survives today and is located just south of the North Branch of the Shenandoah River. The Meem’s had traditionally farmed their acreage with the aid of more than a hundred slaves and were among the wealthiest families in the valley.

Photo of Mt. Airy Plantation in Mount Jackson

The Meem’s household was renowned for their hospitality and on many occasions hosted Civil War Generals and other wartime celebrities. Jedediah Hotchkiss, Stonewall Jackson’s mapmaker, spent some time there waiting with other recruits while Jackson attacked Nathaniel Bank’s troops at the First Battle of Kernstown in March 1862. On March 20th he noted they had “marched to ‘Mount Airy’ the celebrated Meem estate.” “Our men found quarters in the large barns and the officers in the house of Gen. Gilbert C. Meem.”

It was noted that the infirmary “was in continual use throughout the war, aside from six months in 1862 when the hospital was not in active use.” There are several interesting considerations regarding why the building was not in continual use. For example, on April 17, 1862, General Nathaniel Banks’ troops drove Jackson’s forces out of Mount Jackson. At the same time, a Massachusetts soldier noted in April of 1862 that the hospital “buildings were admirably contrived and constructed. He stated they were “perfected ventilated, and yet warm.” He also noted the “hospital flags were still flying, but the 500 sick Rebels convalescing there had been removed ten days previous.” Having done so this would have isolated the now empty hospital behind Union lines.

Additionally, in early June of the same year, Stonewall’s Army was driven back up the valley and through Mount Jackson by General John Fremont’s Army. Once again, the town of Mount Jackson would fall to a Union legion. Following Jackson’s victories at Cross Keys and Port Republic, Stonewall abandoned the valley completely, crossing over the Blue Ridge at Brown’s Gap, on his way to reinforce Robert E. Lee’s army during the Seven Days Campaign.

Soldier’s Statue at Our Soldiers Cemetery in Mount Jackson

The Mount Jackson facility had always been intended as a “wayside hospital.” Is was not designed to be a “permanent treatment facility for the badly wounded.” As a result, early in the war the hospital was mainly used to treat diseases. The hospital would tend to the sick and wounded from Jackson’s Valley Campaign of 1862. as well as casualties from the Battle of Antietam later that same year. It is reported that the “hospital treated at least one hundred patients almost every month for the first two years of the war.”

Following the Battle of Gettysburg some “8500 wounded Confederate soldiers, plus 4000 Union prisoners” passed by the doors of the Mount Jackson Hospital. In July the five hundred bed facility had collected some 667 patients. More that two hundred of these were there for gunshot wounds. Without adequate medical supplies, though, the hospital was operating far beyond it limitations. Still. in the month of July, 1863, just thirteen patients perished at the facility.

In the wake of his defeat at the Battle of Third Winchester, in late September 1864, Jubal Early withdrew his army back through the town of Mount Jackson as well. When General Phil Sheridan’s Army appeared in the town it was noted that the hospital was “filled with Confederate wounded.” Sheridan ordered that the third building, which was vacant at the time, be burned. Following the war, the two remaining buildings would be disassembled by members of the 192nd Ohio Infantry Regiment. They would use these building materials to construct a barracks for occupation forces at Rude’s Hill, just south of the town.

Entrance to the Our Soldiers Cemetery

Mortality rates were always high at the facility mostly due to the lack of medical supplies. Recognizing that not all patients could be saved from their illnesses or their wounds, Colonel Rinker had also donated land on the opposite side of the Valley Pike for two cemeteries. In the first, which was placed adjacent to the Valley Pike, some four hundred war dead, from eleven southern states, would find their final resting place.

Plaque Memorializing Confederate Soldiers Who Died at Mount Jackson Hospital

Dr. Andrew Meem, himself, would become ill in February 1865. Andrew was taken south to the Harrisonburg General Hospital where medical supplies were more readily available. Treatment failed, though, and the doctor soon expired at age forty-one. The doctor’s wife, Ann, who had served as his assistant at the hospital, would return to Mount Jackson. Here she helped to organize the Ladies’ Soldiers and Aid Organization which provided food, clothing, and supplies to Confederate soldiers.

On May 10, 1866, the third anniversary of Stonewall Jackson’s death, a “Memorial and Decoration Day” celebration was organized by that same Soldiers and Aid Organization of Mount Jackson. As part of the ceremony a service was conducted in a local church. Here Henry Kyd Douglas, a surviving member of Jackson’s staff, made an address to commemorate the occasion. Following the church observance “ladies, gentlemen, and children as well as many ex-Confederates, all marched to the cemetery ¾ of a mile north of town to place those wreathes on each of the 400 graves.” Today a ceremony takes place with the placement of Confederate Battle flags on each of the graves on Veteran’s Day each year.

Initially the Confederate dead had had their final resting place denoted in various ways, including boards stuck in the ground with the soldiers’ names, units, and death dates scratched upon them. By the time the United Daughters of the Confederacy were able to construct a monument at Our Soldiers Cemetery in 1908 only three of the original markers still stood, all of whom were undoubtedly Gettysburg related casualties. A list of the majority of the casualties was generated and commemorated. Some one hundred and more are still unknown.

Confederate Veteran’s Day 2018 at Our Soldiers Cemetery in Mount Jackson

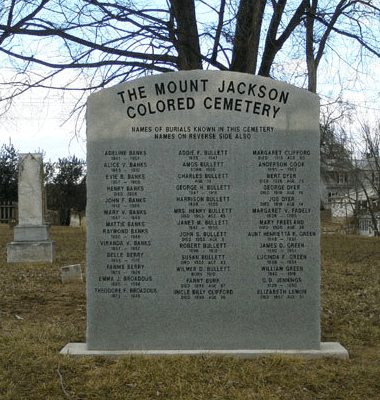

Mr. Rinker was also responsible for the creation of a second cemetery located across the railroad tracks and adjacent to Our Soldiers Cemetery. This site would provide a final resting spot for African Americans and ex-slaves. Over the years many of the markers were lost and the identity of many of the occupants vanished. In 2004 a new memorial marker was placed denoting the names of all of the individuals that could be recovered. Here they dedicated a new memorial, retaining the cemetery’s traditional name, “The Mount Jackson Colored Cemetery”.

African American Memorial in Mount Jackson

Hotchkiss, Jedediah. Make Me a Map of the Valley: The Civil war Journal of Stonewall Jackson’s Topographer. Southern Methodist University Press. Dallas. 1973

Sharpe, Hal F. Shenandoah County in the Civil War: Four Dark Years. The History Press. Charleston, S.C. 2012.

Tanner, Robert G. Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. ’Stonewall’ Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Spring 1862. Doubleday and Company. Garden City.

http://archives.countylib.org/tour/items/show/62

Many of the photos were provided by Brian Swartz. http://maineatwar.bangordailynews.com/