This is the story and Civil War journey of five brothers, William, Charles, Leander, Lewis, and Eugene Goldsborough, all of whom were born in the town of Graceham in Frederick County Maryland. They were the sons of Leander and Sarah Goldsborough. The Goldsborough’s were a prominent family in Maryland with a long history, particularly in Frederick and Talbot Counties. Many participated in state and local politics, and in Maryland society. Several members of the family held prominent positions, including Robert Goldsborough, who was a U.S. Senator, and Phillips Lee Goldsborough, who served as governor of the state.

Leander and Sarah Goldsborough were both geographically and diplomatically active. The family crossed the country with their young household “behind an ox team” along the California Trail when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in early 1848. Integrated into their adventure was a trip down the Mississippi River, a meeting with Kit Carson, and encounters with the Mormons in Salt Lake City. Their exertions at prospecting, however, were downright disappointing and two years later they returned to Maryland sailing around Cape Horn and resettling in their native state.

In the early 1850s the Goldsborough family was keenly involved in the Lopez expedition to liberate Cuba. The goal of this excursion was to annex the island to the United States. The expeditions were largely supported by pro-slavery factions in the South and were aimed at overthrowing Spanish colonial rule and establishing Cuba as a slave state. This may speak volumes regarding the family’s stance on slavery.

Son Charles had been born on December 16, 1834. Following the family’s failed trip to the West Coast and the Lopez expedition he began to study medicine in his father’s office and at the University of Maryland in 1855. On March 4, 1857, he married Mary Neely, and moved to Hunterstown, in Adams County, Pennsylvania. The couple had two daughters: Grace Annie, born January 8, 1858, and Mary McConaughy, born March 4, 1860. His wife Mary expired six days after the birth of their second child from complications originating in childbirth. Their daughter Mary perished from disease just six months later

When the Civil War broke out, Charles journeyed back to his home state and joined the 5th Maryland Infantry as a surgeon in September of 1861. The regiment was initially assigned to Camp at LaFayette Square in Baltimore. In late October of that year, following the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, Charles was “assigned to duty at the old barracks at Frederick City, Maryland, to assist in establishing a division hospital for Gen. Bank’s boys, who were about to go into Winter quarters in and around that place.”

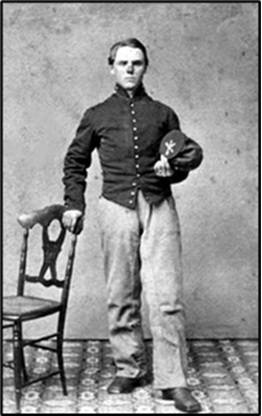

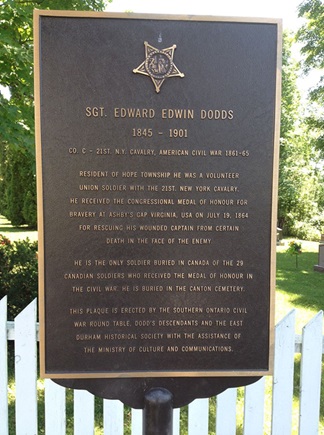

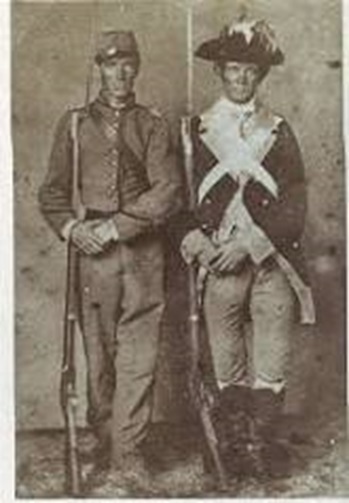

Dr. Charles Goldsborough of the 5th Maryland.

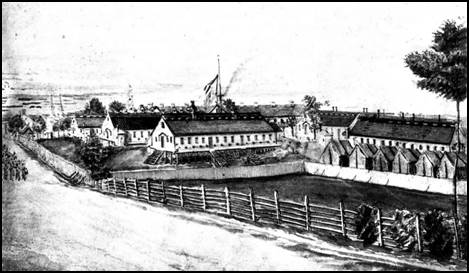

The Frederick military hospital was established on the old Hessian Barracks grounds on South Market Street. Charles noted, “It was not a great while before our hospital had grown to considerable size, with a fine medical staff in attendance, as an open Winter created a large amount of sickness in the various camps, some of which were very unfavorably situated.”

“The existing structures on the property consisted of a pair of stone buildings and at least five frame buildings, set on four acres of ground and enclosed by a board fence.” In June 1862, the hospital was officially designated as the United States General Hospital #1. By then, additional hospital ward buildings had been added. William W. Keen, an Assistant Surgeon at the hospital, noted that the new barracks were “finely ventilated using a ridge-ventilation system, and could accommodate eighty patients.”

Charles chronicled that “the boys had a nice time during the Winter of ’61-62 (barring the mud, that was generally knee deep) attending balls and parties and making love to…THE PRETTY GIRLS OF MARYLAND, and not a few captures were made from our ranks by the dear creatures.” He also observed that “it was a hard Winter upon the troops, as smallpox, measles and typhoid fever raged with considerable severity, and many a poor fellow got no farther in his effort to suppress the rebellion than the little cemetery on the hill beyond the barracks.”

U.S. General Hospital #1 in Frederick, Maryland where Dr. Charles Goldsborough was stationed.

As spring returned to Maryland Charles was still serving at the hospital in Frederick when “Gen. Banks commenced his memorable campaign up the Shenandoah Valley, followed by his equally memorable retrograde movement out of it into Maryland again, which we consoled ourselves was one of the most masterly retreats in the annals of warfare.” All this was provoked by General Stonewall Jackson’s “masterly” Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

According to surgeon Goldsborough: “The summer passed away, and the bloody battles on the Peninsula had been fought and Pope defeated, and our hopes and fears were chasing each other from zero to blood heat and back again like the mercury in the thermometer. Our hospital was no longer a division, but a general hospital, and one of the very best in the country.”

On Sept. 5, 1862, Charles was Officer of the Day at the hospital. At this time General Robert E. Lee was preparing to cross the Potomac with his army. It was hoped in so doing they could recruit native Marylanders to the Confederate cause. “Near midnight that day Charles received a dispatch from General Nelson (Dixon) Miles at Harper’s Ferry stating Lee’s army will enter Frederick tomorrow. Any property that you do not want to fall into the hands of the enemy had better be destroyed. Our communications will soon be destroyed.”

The following day Dr. Goldsborough recalled “there was a commotion at the entrance of the grounds among the group of watchers as a single horseman clad in butternut dashed through the gate, up to and in front of where we were sitting, reined up his horse, brought his carbine to his shoulder, covering Dr. Heany, who had risen to his feet and stood at the head of the stairs with his badge as Officer of the Day over his shoulder…” The Confederate cavalryman declared: “I demand the surrender of this post in the name of Gen. Lee and the Confederate States of America, still covering Dr. Heany with his carbine.”

“The Doctor turned to me and asked, ’What had I better do?’”

Goldsborough responded saying, “If you are prepared to defend the place, tell the man so; if not, surrender it.”

“Then I surrender, sir,” Dr. Heany replied hurriedly.

The Confederate cavalryman “smiled at the Doctor’s embarrassment and informed us he belonged to White’s 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry. He explained he was the advance of General Lee’s Army. He advised us to keep within the grounds until the army had passed and taken possession of the city, and then rode off, after promising to send a guard.”

“On Tuesday we were paroled and permitted to go upon the streets and to our hotels; but what a change had come over the city. Everywhere was found the butternut instead of the blue. The general behavior was good and rarely did any act of outrage or disturbance occur. The strictest discipline was enforced in every case. In fact, the common soldier appeared too wretched and inanimate to care for anything but to eat and sleep.”

Charles remembered that the Confederates “threw themselves down anywhere and slept. They ate anything and everything that was offered them, and about 800 staid in the hospital when the army moved away. How men famished and footsore could fight as they did was a question, I asked myself over and over again…the discipline was perfect and cruel towards the private soldier.”

“Just as suddenly General Ambrose Burnside’s infantry swarmed through the city, driving the Confederates before them toward South Mountain. Soon thereafter commenced the series of terrible battles of this campaign at South Mountain and Antietam”.

Following the Battle of Antietam, Dr. Goldsborough spent an extended period tending to wounded soldiers at the general hospital in Frederick. There is a hint he may have been sent briefly to Fredericksburg following the fight there, but I was unable to confirm that. What I can validate is that Charles was reassigned to the 5th Maryland Infantry and spent the late winter and spring of 1863 on Maryland Heights at Harper’s Ferry where his regiment performed guard duty while recovering from their “terrible losses” sustained at Antietam. On June 2nd, 1863, they were transferred to General Robert Milroy’s command at Winchester, Virginia.

Brother number two, William Goldsborough, was born October 6, 1831, in Frederick County, Maryland as well. “From early manhood the career of Major Goldsborough was replete with the stress and storm of arms. As a lad he ran away from home to enlist for the war against Mexico but was overtaken in Baltimore and taken back home.” He was fifteen years old at the time.

Prior to the Civil War, William was a member of the Baltimore City Guard Battalion which was a prominent militia unit in Baltimore. It was part of the Maryland Volunteer Militia’s First Light Division, 53rd Infantry Regiment, Second Brigade. In 1859 elements of the City Guards, under the command of George Steuart, participated in the suppression of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Militiamen forced John Brown to abandon his positions in the armory forcing them to fortify themselves in “a sturdy stone building”, the fire engine house, which would later be known as John Brown’s Fort. William, an officer in the Baltimore City Guard Battalion, would be one of the first to enter the armory at Harper’s Ferry.

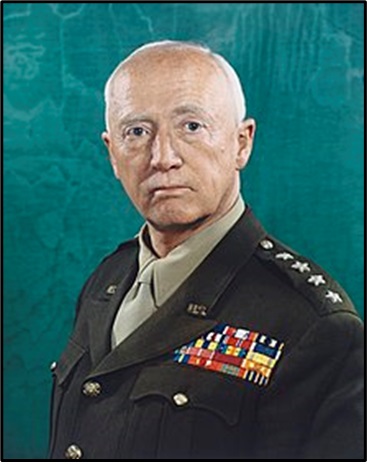

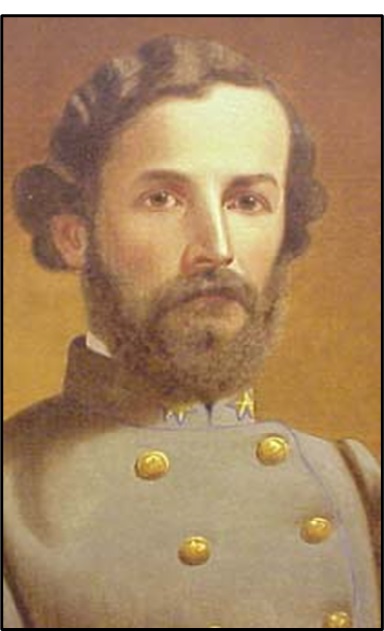

Major William Goldsborough

William worked for a time as a printer in Baltimore before the war. In May 1861 30-year-old William enlisted as a private in Captain Edward R. Dorsey’s Company C of the First Maryland Confederate Infantry. The regiment arrived at Camp Bee, one half mile northwest of Winchester on Apple Pie Ridge, and was brigaded with the 10th and 13th Virginia as well as the 3rd Tennessee on June 27, 1861. Colonel Arnold Elzey, being the senior colonel, was appointed as the brigade’s commander. At the Battle of First Bull Run private William W. Goldsborough and the 1st Maryland would see the elephant for the first time. They would fight at Chinn Ridge late in the afternoon of July 21. Here they would assist in routing Colonel Oliver O. Howard’s Brigade from the field and join in the pursuit of the Union Army.

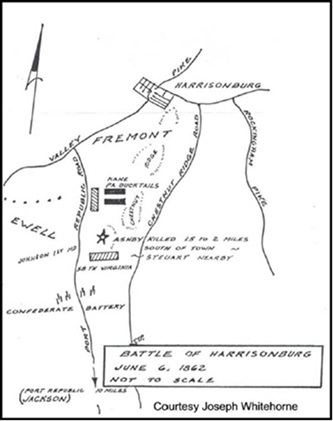

Promoted to Captain in Company A of the 1st Maryland, William would participate in Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign. His regiment would fight against the 1st Maryland Union Regiment on May 23, 1862, at Front Royal. (Reports asserting that William captured his brother Charles at Front Royal are obviously false as he was clearly stationed at the hospital in Frederick, Maryland.) This is the only time when two units, designated by the same numerical order and state, fought each other in a battle. Two days later his battalion would participate in the attack on the left flank of General Nathaniel Banks Division at the Battle of 1st Winchester and on June 6th, the Marylanders would fight a successful rearguard action at the Battle of Harrisonburg, or Good’s Farm, where cavalry leader General Turner Ashby was mortally wounded. Forty-eight hours later they were part of General Richard Ewell’s defensive line at the Battle of Cross Keys.

The regiment also participated in the Battle of Gain’s Mill and Malvern Hill during the Peninsular Campaign. Stonewall Jackson while on his march to Pope’s rear at Manassas, in August 1862, placed Colonel Bradley T. Johnson in command of General John Jones’ Brigade in the Stonewall Division. “General Jones having been disabled Johnson assumed command and put Captain William Goldsborough in command of the 48th Virginia Regiment. At Second Manassas Jone’s brigade “reduced to about 800 effectives, for nearly two days fought desperately and heroically at the railroad cut against Fitz John Porter’s Corps, holding its ground to the end, repulsing many attacks in heavy force and often making counter charges.”

During the Battle of Second Manassas, Captain Goldsborough was severely wounded with what was believed to be a mortal injury. “Careful nursing by hospitable Virginians in the Bull Run mountains restored him in time (in the latter part of 1862) to secure the captaincy of Company ‘G,’ 1st Maryland Battalion, being shortly afterward elected major, under Lieutenant-Colonel James R. Herbert.” The 1st Maryland Infantry would, however, muster out at Richmond at the end of its term of service on August 17.

After the disbandment of the 1st Maryland Infantry, the soldiers of the former regiment found themselves in a precarious position. They were unable to return home to Maryland, having effectively committed themselves to the Confederacy for the duration of the war. With little choice many joined artillery, or cavalry units, while others waited to form a new Maryland Infantry Regiment. This new unit was initially known as the 1st Maryland Battalion until it was officially designated as the 2nd Maryland Infantry in January of 1864.

In early summer 1863, the1st Maryland Battalion was assigned to General George H. (Maryland) Steuart’s Third Brigade in Major General Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division. This was part of General Ewell’s 2nd Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. On June 12, 1863, the Marylanders crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains through Chester Gap on their way to Winchester.

The third brother, Eugene, born in 1844, is somewhat of a mystery. I can place him as a seventeen-year-old private in Company A of the 1st Maryland Infantry. I know he is with the regiment at 1st Bull Run and participated in both Jackson’s Valley Campaign and the Peninsula Campaign in 1862. When the 1st Maryland Infantry was disbanded, Eugene left Confederate service. In March of 1863, however, he re-enlisted in Company C of Harry Gilmor’s 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion. He would have participated with Gilmor’s cavalry unit at the 2nd Battle of Winchester and at Gettysburg.

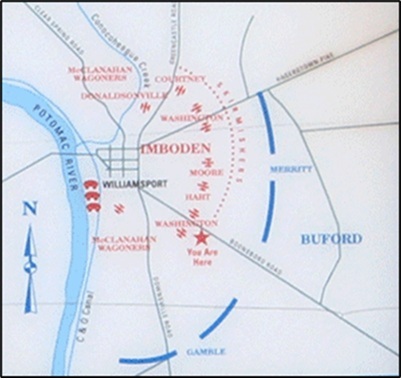

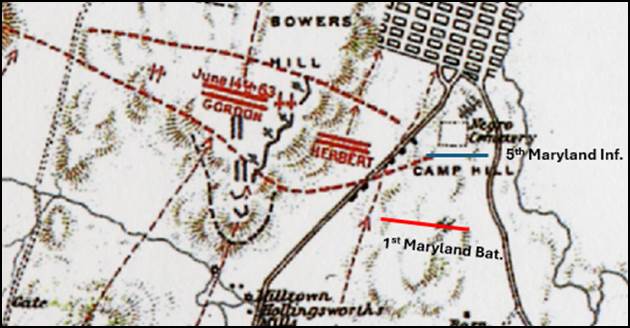

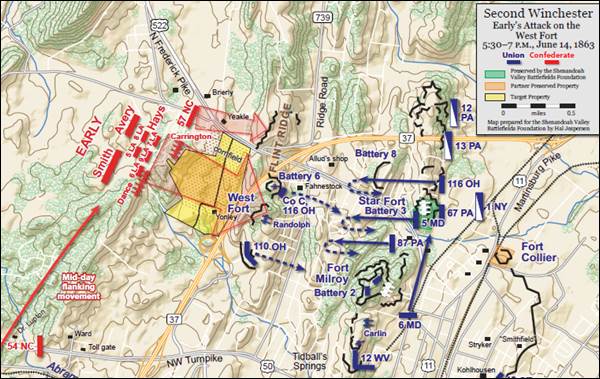

Position of the 5th Maryland, Union, and 1st Maryland Battalion, Confederate, at Winchester on the Afternoon of June 14.

By the afternoon of June 13, 1863, the combat at the 2nd Battle of Winchester had become widespread. Charles recalled that “the enemy now sent forward their infantry, and we met a foe that we could retaliate upon. With variable success we fought them during the day. At times we pushed them back and then were compelled to give way. Gordon had charged Elliot on our right and forced him back to Winchester, and our brigade took a position on the south of the town, in a cemetery, which we held when night came upon us.” The cemetery was locally known as Camp Hill. “The 2d Md. of the enemy had fought in the immediate front of the 5th Md, of our army, and was in some cases brother against brother.”

“At early dawn on the 14th the rain ceased and the sun clear and beautiful on that Sabbath morning; but the infantry soon commenced their firing along the whole line with a repetition of yesterday’s results the 2d Md. returning to the 5th Md. on our side.” Charles, aware that his brother William had been promoted to Major in the 2nd Maryland, borrowed a spyglass from a friend, and “examined the rebel line as it came to the attack”, and thought he recognized William leading the assault on a “sorrel horse.” As the officer appeared to be in command, he believed it could not be him. The officer “rode along the rebel line on this horse several times, and our boys behind the gravestones were taking deliberate aim at him in firing. Presently the sorrel horse and rider went down, and a shout went up along our whole line, and we saw nothing more of the sorrel horse or rider.” It was evident to Charles that the wounded rider was not his brother William.

William recalled the enemy withdrew “until they reached a stone fence about two hundred yards from the town, when the fight was renewed, and continued several hours the enemy holding a position in a cemetery lot. This the Marylanders finally drove them from with loss. We afterwards ascertained it was the Fifth Maryland we had encountered.” At no point does William acknowledge that his brother Charles was a member of that Maryland regiment.

Meanwhile General Jubal Early had secretly moved the brigades of Harry Hays, Avery, and Smith and a sizable number of artillery pieces out to the west of Milroy’s forts. About 5:00 p.m. Early was satisfied that all the necessary preparations had been completed, and he ordered his artillery rolled out of the woods and commenced bombarding West Fort. Including Griffin’s guns, twenty artillery pieces opened on the fortification. The fire continued for about forty-five minutes. Charles noted “the battery on Flint Hill worked savagely but was overmatched.” Cornelia Peake McDonald’s home which was located directly beneath the track of the artillery fire coming from Griffin’s guns, recorded in her diary: “It seemed as if shells and cannon balls poured from every direction at once.”

A little after 6:00 p.m. General Harry Hayes ordered his Louisiana Tigers to charge the fortifications. Most of these men had fought at the 1st Battle of Winchester under General Stonewall Jackson. The 6th, 9th, and 7th Louisiana Infantry was in the front line followed by the 5th and 8th. Bolting out of the trees down the hill they went stopping only occasionally to discharge their muskets. Inside the fortifications before them was the 110th Ohio each man armed with Henry repeating rifles. Undaunted, they charged on until they reached their entrenched foe. Finally, “the Federals began to give way, and pretty soon the Louisianians with their battle flag, appeared on the crests charging the redoubts.” “Early had taken two of the forts and tuned their guns on the remaining two still held by the enemy.”

Jubal Early’s Attack on West Fort Led by the Louisiana Brigade. (SVBF)

Charles began to make his way to the forts and he recalled he had barely reached his “destination when Hays made his charge, and our forces fell back in some confusion, artillery and infantry– supports all in one mass, while the rebels gave us shot at short ranging from our own guns.” The 5th Maryland was part of an unsuccessful counterattack which failed to retake West Fort. “The infantry firing now ceased, but heavy cannonading continued until 10 o’clock at night, when all became quiet.”

At about 9 p.m. a formal council of war was held. Milroy and his officers made the decision to try to “cut their way through” to Harpers Ferry on the old Charles Town Road. At about 1 a.m. the retreat commenced with General Washington Elliot’s Brigade leading the withdrawal, followed by Colonel William Ely’s Brigade, and then Colonel Andrew McReynolds. “The head of the column had reached Carter’s house, about 4 miles outside of town on the Martinsburg pike, before the tail end had got out of the fortifications.”

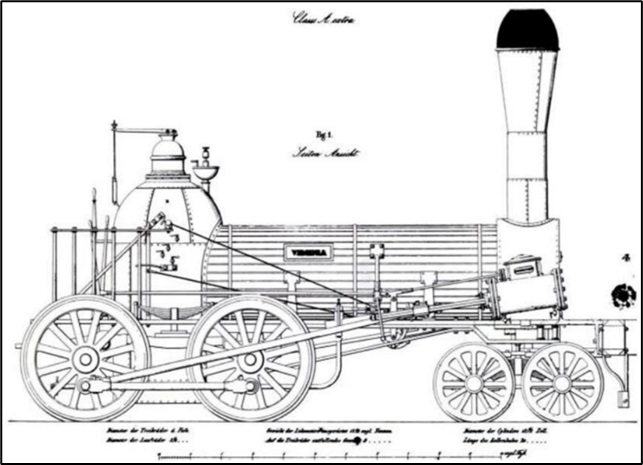

Sometime around 3:30 a.m. on June 15, General Edward Johnson’s skirmishers bumped into the van of Milroy’s retreating column near the intersection of the Valley Pike and Charles Town Road. Milroy faced his column to the right on the pike and prepared to fight his way through by attacking the enemy. Meanwhile Johnson deployed his regiments along Milburn Road as they came up and advanced them to the railroad tracks. Here he placed two artillery pieces from the 1st Maryland Artillery CSA on and around the Charles Town Road railroad bridge.

Charles recalled: “Elliot was met by some of Johnson’s Division that had been pushed around from the south of town and immediately opened fire upon us. Many of Elliot’s Brigade was already past and continued on. Col. Ely formed his brigade as well as he could considering the confusion ensuing, while the Ohio regiment and a West Virginia regiment and the 67th Pa. also formed a line and charged the guns that were playing upon us over a clover field, but Walker’s Brigade supporting them, we were driven back. In the meantime, our line was melting away by squads, as everyone knew it was a forlorn hope. Milroy showed his courage to the last by riding up and down the line addressing the men in language more forcible than elegant.”

“A second charge was made, but the clover was high and tangled, the men tired and worn out from fighting and marching, and it lacked spirit; but the men fought notwithstanding. It then become a rout, and sauve qui peut (meaning a general rout) was expressed on most faces, if not spoken. It was now getting towards morning, and the 5th Md., 18th Conn., and 87th Pa., or such of them that remained together, finding themselves cutoff, surrendered; also, an Ohio regiment just across from us in a woods. These regiments had been the nucleus of the battle on our side while the rest were leaving. My recollection of the last I saw of Milroy was after the last repulse. He galloped from the field with some others off to the left, with the most painful expression of face I ever saw. I hoped he might escape, knowing the bad feeling towards him by the rebels, and he did, though I thought at the time his show was a poor one.”

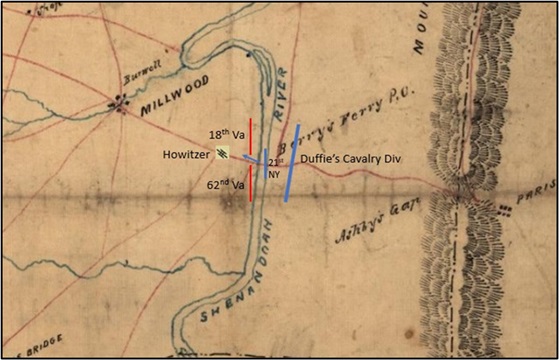

Charles was captured near Carter’s Woods. (Map courtesy SVBF)

“At daybreak of the 15th Major Goldsborough put his skirmishers in motion and proceeded cautiously through the streets of Winchester without encountering the enemy. The Second Maryland skirmishers, apart from that portion of Company A under command of Lieutenant George Thomas, immediately took possession of the Star Fort, capturing some two hundred prisoners.” “The Star Fort for the day was made a receptacle for prisoners.” William was undoubtedly in Winchester, possibly at Star Fort, when his brother Charles was captured four miles to the east at Stevenson’s Depot.

Charles was apprehended near the Carter Farm and marched back to Winchester. Here he found his rebel brother, William, who had been appointed Provost Marshal of the town “for gallantry displayed in the fight.” A provost marshal’s responsibility was to inventory captured supplies and register prisoners. Since the 2nd Maryland did not fight at Stevenson’s Depot this is undoubtedly how the two brothers met. The report that William physically captured Charles is without doubt inaccurate.

The fighting at Winchester had produced nearly six hundred wounded which would have kept doctors from both sides busy. Charles recalled “obtaining a pass and parole” and setting “about collecting our wounded from the field and moving them to the Taylor Hotel.” “Surgeons and chaplains were allowed to go about at will.” Not being regarded as prisoners they were “sheltered in nearby houses” in Winchester.

On the morning of June 20th Charles, along with the remaining surgeons and chaplains, were ordered to gather at Winchester’s Union (Ion) Hotel and “await further orders.” The entire assembly was soon put into march column and pushed south along the Valley Pike. They were told their destination was Richmond. One of Charles’ fellow captives, Reverend George Hammer of the 12th Pennsylvania Cavalry, recorded that many of the men were “half-clad, many shoeless and hatless and unfed.” “Nothing to eat but what we begged or bought off citizens who hated us intensely…”

The journey to Staunton covered ninety-six miles and took four and a half days to complete. The exhausted, dust covered, and foot sore men were segregated into groups of eighty and loaded into freight and cattle cars belonging to the Richmond Central Railroad and shipped off to Richmond. The passengers were not given any rations, received very little water, and they were not allowed any stops to relieve themselves. The trip would take twenty-four hours to complete.

Charles and the other surgeons had been led to believe they would be quickly “passed through to the United States.” Instead, they marched to Libby Prison where they were registered and examined by the prison inspector. All their possessions were taken from them, even the ones that might be used to ease the suffering of the sick and injured. Charles would remain here for the next four months, all the while trying to negotiate with his captors an exchange of surgeons currently confined to both Union and Confederate prisons. He would linger in Libby Prison until October.

William, on the other hand, was able to continue his journey north with the rest of the 2nd Corps. Lieutenant Colonel James Herbert commanded the 1st Maryland Battalion which would bring some 400 men to Pennsylvania and to the field of battle at Gettysburg. Major Goldsborough was second in the line of command.

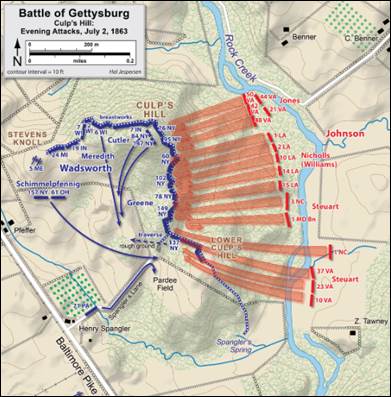

General Johnson’s July 2nd Attack on Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg. (Wikipedia)

The 1st Maryland Battalion would not be involved in the fighting on the first day at Gettysburg. On July 2nd, however, Confederates attacked Culp’s Hill, with the 1st Maryland, the 10th, 23rd and 37th Virginia regiments, and 3rd North Carolina, assaulted Union breastworks, defended by General George S. Greene’s Brigade of the 12th Corps. The Confederates were initially able to breach the works and drive out Green’s men and hold their position until the following morning. Lieut. Col. Herbert was wounded three times on July 2nd as the battalion captured the lower defenses on Culp’s Hill. Major William Goldsborough would then take over command of the unit.

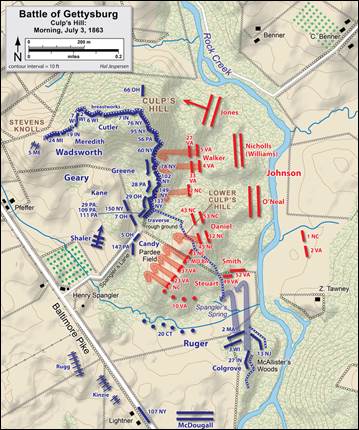

General Johnson’s July 3rd Attack on Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg. (Wikipedia)

The next day the Marylander’s launched a second attack on what is now called the Pardee Field. Late on the morning of July 3, General Johnson ordered a bayonet charge against the well-fortified enemy lines. “Steuart was appalled, and was strongly critical of the attack, but direct orders could not be disobeyed.” “I saw in an instant the object of the movement, and told Captain Williamson, “It was nothing less than murder to send men into that slaughter-pen. Captain Williamson agreed with me, and, moreover, said that General Steuart strongly disapproved of it, but that the order from General Edward Johnson was imperative.”

The battalion’s attack on the Pardee Field failed. “The Third Brigade attempted several times to gain control of Culp’s Hill, a vital part of the Union Army defensive line, and the result was a ‘slaughterpen’, as the First Maryland and the Third North Carolina regiments courageously charged a well-defended position strongly held by three brigades, a few reaching within twenty paces of the enemy lines.” Ironically, one of the units opposing them was the 1st Maryland Eastern Shore Regiment, once again a situation forcing brother to fight brother. A noteworthy example was cousin versus cousin as Color Sergeant Robert Ross of the Union 1st Maryland Eastern Shore regiment fought against his cousin, Color Sergeant P. M. Moore of the Confederate 1st Maryland regiment. Moore was wounded several times during the struggle.

So severe were the casualties among his men that Steuart is said to have broken down and wept, “wringing his hands and crying my poor boys”. At Gettysburg the 1st Maryland Battalion lost 52 killed, 140 wounded, and 15 missing, totaling 207 casualties of the 400 men engaged.

Major Goldsborough, who had taken over command and led the unit in combat on July 3, was among the wounded. A bullet “ripped into the left side of his chest entering at the third rib, passed through his lung and exited out his back.” When the Confederates were pushed back, his comrades carried him to a private residence with three other wounded officers and left them there. Most, including Lieutenant George Booth, “took their last farewell of Herbert and Goldsborough, whose wounds seemed to forbid any hope of recovery.” Following the battle Major Goldsborough and Lieut. Col. James Herbert were both captured and transferred to Camp Letterman along with some 6800 other confederate wounded. Both were later transferred to Fort McHenry in Baltimore for further treatment and then on to Fort Delaware as prisoners of war.

Meanwhile, Charles, who was still serving time at Libby Prison in Richmond, had repeatedly petitioned his captors for parole so that he could effectuate an exchange of captured surgeons. In October he finally received the following parole:

“Richmond, October 20, 1863.

“Dr. Charles E. Goldsborough has permission to go North, upon his giving his parole to honor to return to Richmond Va., withing forty days, if he does not secure the acquiescence of the Federal authorities in the following propositions, to wit: That all surgeons on both sides shall be unconditionally released, except such as have charges preferred against them. Such a proposition is to be understood as embracing not only those already in captivity, but all surgeons who may hereafter be captured.

Ro. (Robert) Ould,

“Agent of Exchange.”

Charles officially accepted his parole and the accompanying conditions and traveled north to Washington D.C. “Aided by Secretary Salmon P. Chase and others, Charles succeeded in affecting the release of about 100 Federal surgeons confined in Libby prison as well several more Confederate surgeons confined in Fort McHenry. Unfortunately, General Ulysses S. Grant and Edwin M. Stanton opposed the exchange, which was unable to do anything toward affecting a general exchange of prisoners.”

Subsequently, Charles returned to his home in Hunterstown, Pennsylvania which is located just five miles northeast of Gettysburg. He arrived in time to attend the “consecration of Gettysburg” on November 19, 1863. He chronicled the scene in his memoir. “This seems strange and almost remarkable, but the great throng was there more to see Mr. Lincoln than to hear what he had to say.” He recalls “the day was an ideal Indian Summer Day, with just enough crisp in the air to make fall clothing comfortable.” The “consecration” he witnessed, of course, included Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address. Ironically, the event took place only a short distance from the spot where his brother William had been wounded on July 3.

In December 1863, Charles was assigned to the medical staff at Fort Delaware. The fort was a former harbor defense facility, designed by chief engineer Joseph Totten and located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River. During the Civil War the United States Army used Fort Delaware as a prison for Confederate POWs. By the time Charles arrived there in December 1863, there were more than 11,000 prisoners on the island.

When Charles disembarked at Fort Delaware, he soon discovered his brother William, who as we mentioned before had been severely wounded and captured at Gettysburg. He also encountered his brother Eugene, who as a member of Harry Gilmore’s Battalion of cavalry, had been captured earlier during an expedition into West Virginia. Both were prisoners of war. It was a remarkable coincidence. It is said that Charles, later in life, would often enjoy telling the story of his unusual family get-togethers and reunions.

In the spring of 1864 Dr. Goldsborough went with his regiment to Bermuda Hundred, on the James River, joining forces commanded by General Benjamin F. Butler. Here he attended to the wounded and assisted in the siege of Petersburg. Charles was himself wounded on July 6, 1864, and sent to Chesapeake Hospital in Hampton, Virginia. This facility was meant for officers, while the larger Hampton General Hospital, consisting of “a network of structures and tents, was primarily for treating enlisted men.”

Following his recovery, it was determined he was unfit for field duty due to a disability acquired in the line of duty. Charles was assigned to Lincoln Hospital, in Washington, D.C., where he remained until August 1865. He then returned to Hunterstown, Pennsylvania where he resumed his medical practice and engaged extensively in farming.

Charles would, on November 14, 1866, marry Miss Alice E. McCreery, and would father ten children. “In politics Dr. Goldsborough, although descended from old Federal stock, early in life embraced the faith of Jefferson and Jackson and always espoused Democratic principles.” “Charles was a member of the Corporal Skelly Post, No. 9, G. A. R in Gettysburg. He died on October 18, 1913, aged 78 years, and is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg.”

In July 1864 William’s life would take a noteworthy detour. In June of that year the Confederate Army had imprisoned five generals and forty-five Union Army officers in the city of Charleston, South Carolina, using them as human shields to stop Union artillery from firing on the city. In retaliation, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered fifty captured Confederate officers of similar ranks to be taken to nearby Morris Island. The Confederates landed on Morris Island in late July of that year where they were to be utilized for the same purpose. The scheme worked as it would enable the exchange of all fifty officers on August 4, 1864.

Major General Samuel Jones, commanding the Confederate Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, then brought 600 additional prisoners to Charleston from Andersonville and Camp Oglethorpe prisons in Georgia, to compel a larger prisoner exchange. In retaliation for the treatment of Federal prisoners, General John Foster asked for a like number of Confederate detainees brought to Morris Island. These men were withdrawn from Fort Delaware and sent south. They would be forever known in the South as the Immortal Six Hundred.

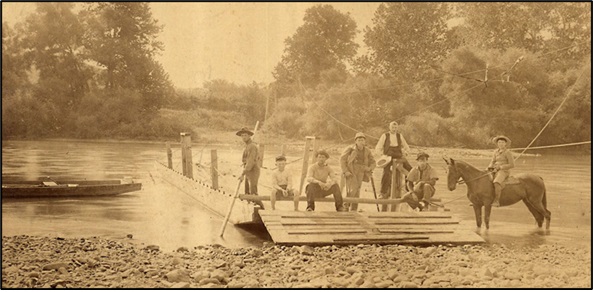

Stockade for Confederate Prisoners on Morris Island.

In late 1864, Major William Goldsborough and 599 other prisoners were ordered to be transferred to Morris Island. Bound for Charleston, the 600 Confederate officers, “faced the worst conditions that they had yet encountered as prisoners.” “Forced to lie shoulder-to-shoulder in the ship’s hold below the water line, one prisoner said that they lay in ‘total darkness, without any clothing and drenched in perspiration’ from the summer heat which was intensified by the ship’s boilers. As the Crescent City rolled in rough seas, all of the prisoners became seasick, leading one on board to describe the ship’s hold as ‘a veritable cesspool’ which the Union guards refused to hose down.” In this environment the Rebs were fed just a “few crackers with a bit of salt beef or bacon” per day. Drinking water was likewise scarce, said one prisoner, and it “had a disagreeable smell and a very sickly taste.”

The Confederate officers were placed in an open stockade on Morris Island in the line of rebel artillery fire. The regiment assigned to guard them during their stay was the 54th Massachusetts, a noted black regiment. Originally commanded by Robert Gould Shaw, they were currently headed by Colonel Edward Needles Hallowell. Hallowell had suffered three wounds in the assault on Fort Wagner but had recovered and would command the regiment for the rest of the war.

Lieutenant Colonel Herbert and Major Goldsborough of the 2nd Maryland “were among the six hundred Confederate officers, prisoners of war, who were placed within range of the Confederate batteries at Charleston, S. C., during the fierce Federal assault on that city; suffering many hardships and privations, having often killed and eaten cats and other animals! What could have been more cowardly and despicable than such treatment to such heroes!”

This standoff continued until a yellow fever epidemic forced Confederate Major General Jones to remove Federal prisoners from Charleston. The Rebel prisoners were transferred from the open stockade at Morris Island to Fort Pulaski at the mouth of the Savannah River in Georgia. On October 23,1864, over five hundred “tired, ill-clothed, men arrived at Cockspur Island.” Early on the emaciated troops received extra rations and were promised extra blankets and clothing. Crowded into the fort’s casemates for forty-two days, a “retaliation ration of 10 ounces of moldy cornmeal and one-half pint of soured onion pickles was the only food issued to the prisoners. Despite the best intentions of the fort’s command, the prisoners never received sufficient food, blankets or clothes” even during winter months.

In March 1865 the survivors were shipped back to Fort Delaware, where twenty-five more succumbed to illness. Major Goldsborough was among the survivors remaining there until after the war ended. The last members of the Immortal 600 were not released until July 1865.

Soon after the war William Goldsborough established the Winchester Virginia Times and the weekly edition of The Evening Star, which published its first issue on Sept. 7, 1865. William sold the paper in 1869 and traveled to Philadelphia to reside. Goldsborough was with the Philadelphia Record from 1870 to 1890. In 1890 William “migrated to the Northwest, settling at Tacoma, Washington. Here he met what was regarded as the roughest gang of printers on the Pacific Coast. Prior to his arrival no one had dared to run counter to them; but as foreman of the Tacoma Daily Globe, he cleared out the gang, unionized the office and made it one of the best on the slope. This feat gained for him the title ‘Fighting Foreman.’”

Upon the sale of Globe, William relocated to Everett, Washington, where he worked for a time at the Everett Herald, and later started the Everett Sun. “About 1894 he returned to Philadelphia, contributing war articles to the Philadelphia Record.” William was obliged to retire in 1896 after being run over by a bicycle. “William’s thigh was crushed, and he was forced to walk with the aid of crutches for the rest of his life.”

After the war, William wrote a book about the wartime service of the Maryland Line which was published in 1869. The 2nd Maryland’s participation in the Battle of Gettysburg gets a good deal of positive coverage between its covers. William died on Christmas Day in 1901. His last request to his wife was “don’t bury me among the damn Yankees here.” His wife honored his wishes, and he died “an unrepented Confederate soldier.” He is buried on Confederate Hill at Loudon Park Cemetery in the city of Baltimore, Maryland.

Unfortunately, Private Eugene Goldsborough continued to reside at Fort Delaware as a prisoner of war. In Early 1865 he became sick and died from disease on February 21, 1865, at the age of 21. He was buried in the Confederate section of Finn’s Point National Cemetery in Pennsville, New Jersey. Originally purchased by the federal government for the construction of a battery to protect the port of Philadelphia, the land became a cemetery in 1863 for Confederate prisoners of war who died while in captivity at Fort Delaware.

Disease was rampant at Fort Delaware throughout the war and nearly 2,700 prisoners died from malnutrition or neglect. Confederate prisoners interred at the cemetery total 2,436 and are buried in a common grave in what was then a huge pit in the northwestern corner of the site. It was officially made a National Cemetery on October 3, 1875, by request of Virginia Governor James L. Kemper, a former Confederate General, who had criticized the poor maintenance of the Confederate grave sites.

Tablet Listing Eugene Goldsborough at Finn’s Point National Cemetery.

Leander Goldsborough, who was born on October 12, 1836, is listed as a Contract Surgeon during the Civil War. During the war, contract surgeons were civilian doctors hired by the army to serve under contract, rather than as commissioned officers. Leander probably served in this capacity during much of the war. The only mention I can find of him is as a member of “U. S. Volunteers at Camp Schofield in Winchester, Va.” He was stationed there until sometime in 1869.

After the cessation of hostilities, Winchester had been placed under the control of the First Military District of Major General John Schofield, beginning in January 1865. This military presence was part of the larger effort to maintain order and enforce federal authority in the South during the early stages of Reconstruction. Leander would have been serving here while his brother William was establishing his newspaper in the town.

Brother five, Lewis Goldsborough, born on February 22, 1840, is listed as a wartime journalist for the Baltimore Sun. Several of his stories can be accessed online which were written by him on several of the major battles fought during the war. Little more is known about him.

The narrative of the Goldsborough family epitomizes the phrase “brother against brother.” Theirs is the story of internal strife and divided loyalties within families, particularly in border states, where brothers were compelled to fight each other due to their allegiance to the Union or the Confederacy. Fortunately, these siblings were never compelled to harm one another though their lives intercepted several times both during and after the war. Undoubtedly the individual journeys and adventures these brothers participated in went far beyond what they ever could have imagined. Still, they persevered and were later able to see the humor amid the tragic circumstances of their reunions especially that at Fort Delaware. Long live the memories of these and all soldiers who fought in the American Civil War.

Sources

Booth, George W. A Maryland Boy in Lee’s Army. Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland Soldier in the War Between the States 1861 to 1865. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, Nebraska. 2000.

Gilmor, Colonel Harry. Four Years in the Saddle. Reprinted By Butternut and Blue. Baltimore, Md. 1866.

Goldsborough, William W. The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army. 1861-1865. Guggenheimer, Weil, & Co. Baltimore, Md.1900.

Murray, John Ogden. The Immortal Six Hundred: A Story of Cruelty to Confederate Prisoners of War. The Confederate Reprint Company. Atlanta, Georgia. 2015.

Wittenberg, Eric and Mingus, Scott. The Second Battle of Winchester: The Confederate Victory that Opened the Door to Gettysburg. Savas Beatie. California. 2016.