And men will tell their children,

Tho’ all other memories fade,

How they fought with Stonewall Jackson

In the old Stonewall Brigade.”

A tiny clutch of Civil War veterans, “dressed in faded and tattered gray uniforms, white whiskers” gathered in Lexington, Virginia on July 20, 1891. It was one day shy of the thirtieth anniversary of the First Battle of Bull Run. Thirty years previous, on that storied battlefield, these warriors had received their baptism of fire. For the members of the “First Brigade” they had also received a label related to the bold stand they had made on Henry Hill. That brand was “Stonewall”, and it was applied equally to them and to their famous leader, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

A diminutive remnant of the Stonewall Brigade congregated on this cool July day to honor their heroic leader. This small band of men, amidst a throng of some thirty thousand spectators, had gathered for what they were calling their “final muster.” They were here, not for individual recognition, but for the dedication of a graveside statue honoring General Jackson.

Graveside Monument to General Stonewall Jackson

In the midst of all the people, and related celebration, this handful of Civil War veterans seemingly vanished. Some thought that these men had grown weary of all the merriment and had returned home to serener surroundings. In actuality this band of brothers had quietly relocated themselves to the cemetery. Following an extended search by event organizers they were finally located near midnight “huddled in blankets and overcoats around Jackson’s statue in the cemetery.”

When these old veterans were asked if, as their honored guests, they would consider relocating to a warmer, more comfortable location they were met with silence. Finally, one of the veterans responded: “Thank ye, sirs, but we’ve slept around him many a night on the battlefield, and we want to bivouac once more with Old Jack.” And that is exactly what they did.

When Civil War came to the Shenandoah Valley in 1861 these men had gathered to offer their service to the defense of the State of Virginia, and to the newly inaugurated Confederacy. On June 13, 1861, the Lexington Gazette described the future representatives of the Stonewall Brigade as “one of the finest looking bodies of young soldiers that have been sent from this portion of the state. … The patriotic fire which animated the breasts of the boys of Liberty Hall in the days of our Revolutionary struggle is still alive in the hearts of their worthy descendants.”

___________

The Regiments of the Stonewall Brigade

(company letter, nickname, where members were from, and first captain)

Second Regiment

Company A – Jefferson Guards, Jefferson Co. WVA, John W. Rowan

Company B – Hamtramck Guards, Shepardstown, WVA, Vincent M. Butler

Company C – Nelson Rifles, Millwood, VA , William Nelson

Company D – Berkeley Border Guards, Berkeley, WVA, J.Q.A. Nadenbousch

Company E – Hedgesville Blues, Martinsburg, WVA, Raleigh T. Colson

Company F – Winchester Riflemen, Winchester, VA, William L. Clark, Jr.

Company G – Botts Greys, Charlestown, WVA, Lawson Botts

Company H – Letcher Riflemen, Duffields community, VA, James H.L. Hunter

Company I – Clarke Rifles, Berryville, VA, Strother H. Bowen

Company K – Floyd Guards, Harper’s Ferry, WVA, George W. Chambers

Fourth Regiment

Company A – Wythe Grays, Wythewille, VA, William Terry

Company B – Fort Lewis Volunteers, Big Spring area, VA, David Edmondson

Company C – Pulaski Guards, Pulaski Co., VA, James Walker

Company D – Smythe Blues, Marion, VA, Albert G. Pendleton

Company E – Montgomery Highlanders, Blacksburg, VA, Charles A. Ronald

Company F – Grayson Daredevils, Elk Creek community, VA, Peyton H. Hale

Company G – Montgomery Fencibles, Montgomery Co., VA, Robert G. Terry

Company H – Rockbridge Grays, Buffalo Forge & Lexington, VA, James G. Updike

Company I – Liberty Hall Volunteers, Lexington, VA, James J. White

Company K – Montgomery Mountain Boys, Montgomery Co., Robert G. Newlee

Fifth Regiment

Company A – Marion Rifles, Winchester, VA, John H.S. Funk

Company B – Rockbridge Rifles, Rockbridge Co. VA, Samuel H. Letcher

Company C – Mountain Guard, Staunton, VA, Richard G. Doyle

Company D – Southern Guard, Staunton, VA, Hazael J. Williams

Company E – Augusta Greys, Greenville community, VA, James W. Newton

Company F – West View Infantry, Augusta Co. VA, St. Francis C. Roberts

Company G – Staunton Rifles, Staunton, VA, Adam W. Harman

Company H – Augusta Rifles, Augusta Co., VA, Absalom Koiner

Company I – Ready Rifles, Sangerville community, VA, Oswald F. Grimman

Company K – Continental Morgan Guards, Frederick Co., John Avis

Company L – West Augusta Guards, Staunton, VA, William S.H. Baylor

Twenty-Seventh Regiment

Company A – Allegheny Light Infantry, Covington, VA, Thompson McAllister

(later transferred to artillery and known as Carpenter’s Battery)

Company B – Virginia Hiberians, Alleghany Co. VA, Henry H. Robertson

Company C – Allegheny Rifles, Clifton Forge, VA, Lewis P. Holloway

Company D – Monroe Guards, Monroe Co., WVA, Hugh S. Tiffany

Company E – Greenbrier Rifles, Lewisburg, WVA, Robert Dennis

Company F – Greenbrier Sharpshooters, Greenbrier Co., Samuel Brown

Company G – Shriver Grays, Wheeling, WVA, Daniel M. Shriver

Company H – Rockbridge Rifles, originally Co. B, 5th regiment, Samuel Houston Letcher.

Thirty-Third Regiment

Company A – Potomac Guards, Springfield, Hampshire Co. WVA, Phillip T. Grace

Company B – Tom’s Brook Guard, Tom’s Brook, Shenandoah Co. VA, Emanuel Crabill

Company C – Tenth Legion Minute Men, Woodstock, Shenandoah Co., VA, John Gatewood

Company D – Mountain Rangers, Winchester, Frederick Co., VA, Frederick W.M. Holliday

Company E – Emerald Guard, New Market, Shenandoah County VA, Marion M. Sibert

Company F – Independent (Hardy) Greys, Moorefield, Hardy Co. WVA, Abraham Spengler

Company G – Mount Jackson Rifles, Mount Jackson area, Shenandoah Co., VA, George W. Allen

Company H – Page Grays, Luray, Page Co. VA, William D. Rippetoe

Company I – Rockingham Confederates, Harrisonburg, Rockingham Co. VA, John R. Jones

Company K – Shenandoah Sharpshooters, Shenandoah Co. VA, David H. Walton

_______________

This gathering of volunteers was channeled into five infantry regiments which included the 2nd, 4th, 5th, 27th and 33rd Virginia, as well as the Rockbridge Artillery. Together they would form the body of the “First Brigade.” Each of these regiments would be unique and, in time, each would earn its own nickname. There was the “Innocent Second” because they never looted; “The Harmless Fourth” for their good camp manners; “The Fighting Fifth” for bad camp manners; “The Fighting Twenty-Seventh” for its high casualty rate; and “The Lousy Thirty-third” for its habit of acquiring body lice.

This “First Brigade” would fight, as was mentioned before, at First Bull Run. In 1862 they would carry their fervor back to the Shenandoah Valley as the Stonewall Brigade and fight in Jackson’s Valley Campaign. They would be heavily engaged at First Kernstown, and by the time the brigade marched off toward McDowell, on May 7, 1862, the unit would number some 3681 combatants, averaging 736 men per regiment. By the end of the Second Manassas Campaign in August of the same year, however, the corps would have just 635 members, and average some 127 per regiment. A couple of the companies would have only two or three attending members.

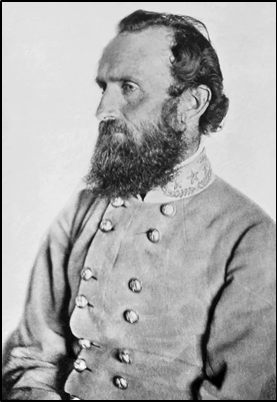

Old Stonewall Jackson

The brigade would fight in the Peninsula Campaign, Antietam, and at Fredericksburg in 1862. They would be at Chancellorsville in the Spring of 1863 where their gallant leader, General Stonewall Jackson, was mortally wounded. They would battle gallantly at Gettysburg, and in the spring of 1864, would be present for the Overland Campaign.

At Spotsylvania Courthouse, on May 12, 1864, the brigade would brawl on the left flank of the “Mule Shoe” salient, in an area that would be known as the “Bloody Angle. Early that morning General Winfield Hancock’s II Corps would launch a massive assault. The fighting was hand to hand and very bloody. All but 200 men of the Stonewall Brigade were killed, wounded, or were among the 6,000 Confederates captured. Losses were so severe that the Stonewall Brigade was unofficially dissolved and consolidated into a single regiment.

When the 1864 Valley Campaign began there were only 249 men left in the five regiments that had originally constituted the Stonewall Brigade. Company A of the 33rd Infantry, for example, had just one man left and he was on sick leave. To add potency nine other regiments were added to the brigade to bolster its effectiveness. William Terry, an original member of the Stonewall Brigade, was appointed as its leader.

The Brigade would fight in all of the battles of the 1864 Valley Campaign under General John Gordon, from Lynchburg to the gates of Washington and back. At the Third Battle of Winchester they would arrive on the battlefield at a critical moment in time to receive and repulse General Cuvier Grover’s attack. Reflexively they responded with their own counterattack. Gordon’s men fought savagely but they were soon overwhelmed.

The Stonewall Brigade was forced to retreat and had barely reached their new defensive line when Federal cavalry slammed into their left flank. General Terry was seriously wounded and the brigade was horribly handled. The 2nd Virginia lost its battle flag and the brigade most of its men. The Stonewall Brigade was, once again, forced to give way. Many would blame them for the Confederate loss at 3rd Winchester.

Following their defeats at 3rd Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Cedar Creek, the Stonewall Brigade returned to Lee’s Army. They served there in the trenches during the Siege of Petersburg and, ultimately, during the Appomattox Campaign. When Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia finally surrendered only 219 of the nearly 6000 men that served in the brigade during the war were present for the surrender.

Back, once again, to that memorable morning of July 21, 1891, when that tiny band of veterans arose early from their impromptu encampment at the cemetery in Lexington. The men enjoyed a light breakfast in anticipation of the day’s events. In due time the Stonewall Jackson monument was unveiled and dedicated. As the ceremony closed the remaining members of Stonewall Brigade “fell into ranks for the last time.” The old soldiers marched leisurely out of the cemetery and out of what they believed was the final chapter of their history. It is reported one of the old soldiers turned to Jackson’s grave and whispered: “Goodbye, old man, goodbye. We’ve done all we can for you!”

These graying survivors of the Stonewall Brigade may have done all they could for General Jackson but this was not to be their final chapter. Their descendants would continue to sacrifice for their nation. With the coming of the Spanish-American War the unit was reconstituted as the 2nd Virginia Volunteer Infantry. Though they did not actually see battle, they were sent to Florida and acted in a reserve capacity. With the end of the conflict they returned to Virginia.

On June 3, 1916, the Stonewall Brigade was transformed, once again, and admitted as an element of the Virginia National Guard. In August 1917, the old Stonewall Brigade was drafted, once again. The descendants of those Civil War veterans became part of the 116th Infantry Regiment, and assigned to the 29th Infantry Division. They were quickly sent overseas as part of the American Expeditionary Force.

The regiment distinguished itself in the Meuse-Argonne offensive in October of 1918. From the 8th to the 22nd of October, the regiment was heavily engaged and suffered enormous casualties. At the conclusion of the offensive, these sons and grandsons of Shenandoah Valley Civil War veterans, found 198 of their comrades had been killed outright. More than a thousand had been wounded, and 59 of these would die from their injuries. To their credit the regiment captured more than 2,000 German prisoners, 250 machine guns, and 29 high-caliber guns. They were mustered out of service on May 30, 1919.

When war came once again to the world, the grandsons and great-grandsons of these Civil War veterans were once again called to duty. The men were assigned to companies in the 116th Infantry, as before, representing the towns and counties of the Shenandoah Valley. Company C originated from Harrisonburg, Company K from Charlottesville, Company I from Winchester, Company L from Staunton, and Company A from Bedford.

The regiment would sail off to Europe in 1944 and were given the honor of being the only civilian unit to participate in the first wave of landings at Normandy Beach. As the landing craft approached Vierville, and the ramps of Company A’s landing crafts were dropped, the men quickly poured onto the beach. “There were no shell holes for cover at Dog Green. Company A had become inert, leaderless and almost incapable of action. Every officer and sergeant had been killed or wounded…. It had become a struggle for survival and rescue. The men in the water pushed wounded men ahead of them, and those who had reached the sands crawled back into the water pulling others to land to save them from drowning, in many cases to see the rescued men wounded again or to be hit themselves. Within twenty minutes of striking the beach A Company had ceased to be an assault company and had become a forlorn little rescue party bent on survival and the saving of lives.”

Many a Virginian is Buried at the American Cemetery at Normandy France

The companies of the 116th that came ashore just east of the Vierville draw suffered the worst, losing an estimated 65 percent of its strength within 10 minutes. Company A was virtually wiped out by heavy German fire and by the end of the day, only 18 of 230 members of the company had avoided injury. This company which had originated from Bedford, Virginia had the highest proportionate D-Day losses of any community in the nation. Out of respect to that community, the National D-Day Memorial was located in Bedford, Virginia to honor their loss. In spite of their casualties they would continue with the courage and sacrifice so typical of them for the remainder of the War. The regiment suffered casualties of 1,298 killed, 4,769 wounded, and 594 missing for a total of 7,113 during the war.

D-Day National Monument in Bedford, Virginia

The Old Stonewall Brigade is active still, currently assigned to the 29th Infantry Division, as part of the Virginia Army National Guard. It is now designated as the 116th Infantry Brigade Combat Team. On its battle flag are ribbons they so proudly earned indicating the many battles they have fought in, including those of the American Civil War.

As we approach Memorial Day, which coincides with Confederate Memorial Day here in Virginia, it is important that we remember all those who gave their allegiance to their state, and to their nation to fight in this country’s wars. As such, it is essential we remember all veterans, even those we may have once fought against during the American Civil War. We are, after all, one nation, now indivisible. It is important we remember our veterans on this and all Memorial Day weekends; no matter the war.

I will be taking a short summer break in order to get the text of a new book ready for publishing. I will see you again in August. Thanks very much for following this blog.

Robertson, Jr, James I. The Stonewall Brigade. Louisiana State University Press. Baton Rouge, La. 1977.

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/wwii/blue-and-gray-at-omaha-beach/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/116th_Infantry_Regiment_(United_States)