Members of Battery H, 1st Ohio Light Artillery

Their line of battle was being shredded by a “fierce fusillade.” Captain Daniel Wilson of the 7th Louisiana noted that Union cannon “belched forth one incessant storm of grape, canister and shell, literally covering the valley, so that the work of attack on our part seemed almost hopeless.” Still, these soldiers marched resolutely on “across the low grounds, right after the battery. From its mouth now, with renewed violence, poured streams of shell and shot, mowing down our men like grass. The earth seemed covered with the dead and wounded.”

Gazing out upon the fields on that warm June morning, Union cannoneers had a nearly unobstructed view to the South Fork of the Shenandoah River to their right. To their front they could see more than a mile over open grasslands. The rooftops of the structures in Port Republic were clearly visible. With Confederate troops swiftly overrunning these open meadows, the acreage to their front was quickly becoming a target rich environment. Over the next few hours it would become a virtual killing field.

Seven Union artillery pieces had positioned themselves on “the edge of a spur, on a plateau that had once served as a coaling, a shallow pit used for making charcoal.” The Samuel Lewis family had used this resource to power their blacksmith shop and the family’s nearby iron furnace at Mount Vernon. Here, seventy-five feet above the surrounding plains, artillery pieces were adeptly positioned to sweep “the wheat fields with blasts of deadly grapeshot.”

View from the Coaling Toward the Battlefield at Port Republic. (Brian Swartz)

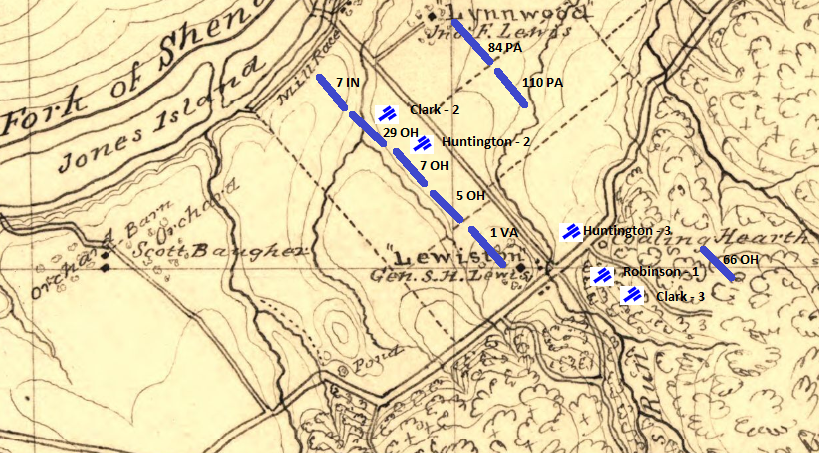

Captain James F. Huntington, who had charge of Battery H, 1st Ohio Light Artillery, noted that the artillery pieces were placed “on a low ridge near where it began to descend to the brook – Clark’s Battery in the coal pit, and a 12 pounder howitzer of Robinson’s in the space between the coal-pit and the road; my left piece in the road itself, and the others extended in the field on the right. The infantry was concealed in the woods along the main ridge to the rear.”

With Jackson’s infantrymen arriving “under cover of the wood on the right as if intending to attack from that direction,” General Erastus Tyler redeployed his thin blue line, into the wheat field to their front, parallel to Lewiston Lane. The right of the line now extended “nearly to the river.” Huntington noted “three of Clark’s and two of my pieces” went with them. Only the 66th Ohio would remain with the artillery for support some fifty yards to the rear. “A few less than 100 men deployed as skirmishers in the woods on the left practically without support.”

Battery H had mustered in at Camp Dennison near Cincinnati, Ohio on November 7, 1861. It consisted of six rifled brass ten pounder cannons. The unit had been assigned to General James Shields’ 2nd Division of Banks’ V Corps, and the Department of the Shenandoah until May of 1862. They were then reassigned to Shields’ Division, Department of the Shenandoah through June of 1862.

Captain Huntington noted the final Union “line of battle, so far as we had one, was formed into two distinct and unconnected parts – on the right the infantry and five guns; then a vacant space; the remaining guns were on the extreme left and really held the key of the position.”

Union Artillery and Infantry Placements (Map Sketch: Peter Dalton)

One of the men manning the guns for Battery H was a thirty-six year old laborer from Cincinnati named John Harrison. Born in Westmoreland County, England, Harrison had emigrated to Boston around 1849 where he met and married a young Irish immigrant, named Anastasia Heffernan. At the time of his enlistment John had fathered three children. One can be sure when John migrated to this country, he never thought he would find himself manning an artillery piece, let alone hammering away at Rebel infantry; and yet, here he was.

By six a.m., John’s commander, Captain Huntington, observed some of Jackson’s infantry and artillery as they began to arrive on the battlefield. “An artillery duel ensued, greatly to our advantage, for although our guns were on higher ground, most of the enemy’s shot passed over us, while our shells exploded among them with deadly effect.”

As it turned out Huntington’s Battery may have been tardy in firing its first rounds. Their artillery pieces discharged what was known as a Schenkl shell. The sabot, which encapsulated part of the projectile, was designed to ensure the correct positioning of the shell in the barrel of the artillery piece. In this case, however, the sabot on the shells were constructed of papier-mâché. Due to all the rain and moisture, the papier-mâché had swollen and some of the shells could not be rammed into the barrels of the guns.

Captain Huntington reported that the rainy weather “has so swelled these sabots that about every other shell would stick in the muzzle of the gun.” Huntington was forced “to set all who could be spared from other duty at paring down the sabots with jack-knives. The artificers and forge drivers were thus employed, and so taken away from the forge they would have otherwise have looked after.”

Meanwhile, General Jackson had dispatched General Charles Winder’s Stonewall Brigade directly into the center of the attack. On the right he forwarded the 2nd and 4th Virginia into the trees along a spine of the Blue Ridge. Their assignment was to dislodge Union artillery situated on the high ground at the Coaling. Though they would mount a direct assault on the position, they would fail in achieving their goal.

Earlier that morning, General Richard Taylor’s Brigade of Louisianans had crossed over a temporary footbridge in Port Republic and gone into camp so they might prepare breakfast. Recognizing that the fighting was intensifying, Taylor rode out ahead of his men in search of General Jackson. “Taylor witnessed the stunning spectacle of the enemy’s artillery working in tandem with the oncoming blue-clad infantry.” Winder’s Brigade “was suffering cruelly. And its skirmishers were driven in on their supporting line.” Taylor realized “it would be no easy matter to defeat such troops…Jackson found he had met men of like metal to his own,”

Upon locating General Jackson, the two men exchanged pleasantries and a measured amount of “ironic humor.” Jackson initially asked Lieutenant Robert English to serve as a guide for Taylor and his brigade. He assigned the Louisianans the task of backing up the troops he had already assigned the mission of seizing the Coaling. General Taylor acknowledged his orders, saluted, and hurried back to get his men moving.

Shortly after Taylor’s departure, though, Jackson’s mapmaker, Jedediah Hotchkiss, appeared. Jackson realized Hotchkiss had an “accurate knowledge of the area” so he also assigned him the task of guiding Taylor’s Brigade. “Take Gen. Taylor around and take those batteries. Pointing to the enemy’s batteries near Gen. Lewis house, which were making sad havoc among our men.”

Jed Hotchkiss noted: “Gen. R. S. Taylor was just then coming up; so I met it and led it, in line of battle, with skirmishers in front, to the right through the woods, until nearly opposite the Gen. Lewis house, when the brigade advanced and charged upon the battery and took it, after being repulsed several times.” “Gen. Wm. B Taliaferro’s Brigade came up, along the western edge of the woods, in time to give the enemy a volley or two by a flank fire. We routed them completely; took at one point a battery of five guns…”

Final Moments of the Fighting at the Coaling

Back at the Coaling, Captain Huntington was examining the seeming success of Union infantry in their assault on the right. His attention was distracted, however, by the appearance of a new Rebel battery. These guns may have belonged to Captain Robert Chew. Huntington was surveying this activity “through a glass when from the woods on our left rushed forth the Tigers, taking the line in reverse and swarming among Clark’s guns. His Cannoneers made a stout but short resistance, as pistols and sponge staffs do not count for much against muskets and bayonets.”

Clark’s three guns and Robinson’s howitzer were quickly captured. Huntington promptly concluded if his guns were to be saved, they would need to be withdrawn immediately. Huntington ordered his first gun limbered up and directed it to the rear. This piece was successfully extracted.

Huntington then shifted his attention to his second gun. “As the team of the next came up, two of the drivers fell, badly wounded, from their saddles. The remaining driver could not control the frightened animals, they broke away and dashed off with the limber, and the piece was abandoned.”

It is probable Private John Harrison had been assigned to this gun. According to pension records, while John was “riding the lead horse of the piece his horse sunk down in the mud and the saddle horse of the swing team fell on him.” As a result, John experienced a spinal injury which caused his left leg to be partially paralyzed. Incapacitated, John was captured by Confederate infantry.

Huntington now directed his consideration to the third piece. “It was under cover and the drivers were loth to leave it. By that time a force had broken out of the woods in our front, and yelling like demons came pouring up the road, straight for our remaining gun.” The force of which he speaks was the 6th Louisiana Infantry. The gun, which had been loaded previously, was discharged by one of the artillerists. “This opened a lane and checked the onset of that particular lot of Tigers for an instant, in which we limbered up the piece, the cannoneers jumped on, and the drivers lost no time getting away with it to the rear.”

The remaining guns on the Coaling would exchange hands three times before they were finally secured by Taylor’s men. One of the Louisiana soldiers stated they had been met with “a terrific fire.” “When they were driven for the third time they were not disheartened, but wiped out.” Five artillery pieces were captured and Federal troops had been routed. Though victorious, Jackson’s men had paid a harsh price for their prize.

Captain Huntington, himself, was left in the dust of his retreating guns. He “felt rather at a loss what course to take.” His “first impulse was to lie down and surrender, as there seemed to be a very poor prospect of reaching cover with a whole skin. But having a wholesome dread of Southern hospitality as dispensed at that period, I concluded to take the chances and was lucky enough to slip out between the bullets.

Private John Harrison, ensnared by Confederate infantry, was one of more than four hundred and fifty Union soldiers captured. Following the battle, Private Harrison was taken to Lynchburg and then on to Belle Isle Prison at Richmond. John was later paroled at Aiken’s Landing on September 13, 1862. He was sent on to Camp Banks in Alexandria, where he was discharged for disability on January 31, 1863. John returned home to his family in Cincinnati shortly thereafter. The debilitating effect of his injury, however, would afflict him for the rest of his life.

The retreat of Federal Troops became wide-ranging. Captured Federal artillery pieces were turned on the fleeing enemy. Colonel Samuel Carroll noted the blow put “the rear of our column in great disorder, causing them to take to the woods, and making it for the earlier part of the retreat apparently a rout.”

Jackson’s forces chased Union troops for more than three miles. In addition to the troops that were captured some eight hundred muskets were picked up as well. Huntington recalled the retreat continued all the way to Conrad’s Store where they discovered General Shields lingering with the other two brigades of the division. They rested here briefly and then resumed their retreat to White House Bridge and Luray.

Losses on both sides were substantial. Huntington reported his loss “had been heavy in killed, wounded and missing. In my battery for example, we lost nearly one third of the men actually under close fire.” Tyler lost more than a thousand men in his army. Jackson’s casualties amounted to over eight hundred. As a result, this battle was the costliest of Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign.

With the fighting over, Stonewall ordered Jedediah Hotchkiss to guide the army to Mount Vernon Furnace on the road to Brown’s Gap. Here they “encamped on the side of a mountain where it was so steep, we had to pile rocks and build a wall to keep from rolling down when asleep.” In addition, heavy rain fell, soaking everyone and adding further to their misery. Such was the price of victory in Stonewall Jackson’s Army.

Thanks very much to Mike Andrew, Great-Great Grandson of John Harrison, for his contributions and his efforts at maintaining accuracy in this dialog.

Browne, Jr., Edward C. Battery H 1st Ohio Light Artillery: 1861-1865. 2012.

Cozzens, Peter. Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, N.C. 2008.

Hotchkiss, Jedidiah. Make Me a Map of the Valley. The Civil War Journal of Stonewall Jackson’s Topographer. Southern Methodist University Press. Dallas, Tx.

Parrish, T. Michael. Richard Taylor: Soldier Prince of Dixie. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill.

Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts: The Shenandoah Campaigns of 1862 and 1864 and the Appomattox Campaign 1865. Boston. 1907.

Pension file of John Harrison, National Archives.

https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/09/death-on-virginias-sacre-soil

http://www.shenandoahatwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Battle-of-Port-Republic-phase-2.jp