Percy Wyndham

On the afternoon of June 6, 1862, a detachment of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry trotted into Harrisonburg, Virginia and turned east along the Port Republic Road, probing for General Stonewall Jackson’s rear guard. The unit’s commander, Colonel Percy Wyndham, was tracking General Turner Ashby. Wyndham had sworn, publicly, that he had intended to “bag him” and he was of the opinion that this was the day he would do it.

Turner Ashby, on the other hand, had taken this moment to dismount his command, giving his men and their horses a well-deserved breather. Their mounts had become appreciably worn by Stonewall Jackson’s ongoing campaign, and were in need of a momentary respite. With Ashby were elements of the 6th, and 7th Virginia Cavalry.

As providence would have it, though, it was at this very moment Colonel Wyndham spotted his opponent and ordered his men to make ready for an attack. Wyndham was anxious “to pluck the budding honors on his crest to weave them on his own.”

General Ashby’s command responded quickly to their predicament, remounting their horses, and preparing to repel the assault. Ashby ordered Major Oliver Funsten to make ready, and as he rode past him yelled: “Follow me.”

Ahead of Colonel Ashby and Major Funsten, however, rode Captain Edward H. McDonald. Leading a small detachment of 7th Virginia Cavalry, he too had spotted Federal troopers as they assembled on the hill opposite them. McDonald knew he must act quickly and had done so. He too had hastily instructed his men to remount, and charge the Federal Cavalry.

The Rebel response to the order was quick in coming. Captain McDonald, racing down Chestnut Ridge, recalled “as we approached them in our charge they began to break away from their line and ran.” Only their commander, Colonel Percy Wyndham, and a few of his men had reacted decorously to the command to charge.

Private Holmes Conrad remembered: “After proceeding about a hundred yards I discovered that the Federal officer [Wyndham] was continuing his advance at a rapid gait but entirely alone; his command remained where I had seen it from the top of the ridge. Then too I discovered for the first time that none of those who had been with me on the summit of the ridge had attended me in my charge.” The two men were racing toward each other, unaccompanied.

Holmes Conrad

According to Conrad: “The sun was shining full on the advancing officer whose sabre, which he handled with a master’s hand, shown like a circle of light. We each approached the narrow ravine between our respective ridges….A sunken rail fence about 3 rails high in the bottom of the ravine was between us….When each of us was about 8 or 10 feet from this place….I dropped my sabre from my hand and let it hang from the sword knot on my wrist and drawing my pistol held it down by my side. The officer had reached the fence which he for the first time saw and halted.”

“The fore legs of his horse were over it. His sabre was held with the point down. He was peering over the horse’s head down at the fence which had impeded him. I gathered rein tightly in my left hand, stuck both spurs into my horse and in a moment had the muzzle of my pistol against the side of the big red nose of the fiercest looking cavalryman I ever confronted. He had an enormous tawny moustache that reached nearly to his ears; large eyes of the deepest blue and these were fastened upon me with a clear, strong gaze without the lease indication of fear.”

“Unwilling to betray my own nervousness by a faltering voice I was content to return his stare for a minute in silence and then said to him ‘Drop your saber!’ I did not tell him to ‘return’ I was unwilling that the point of that formidable blade should be removed, even for a second from its earthward direction. He did not instantly obey. I said: ‘If you don’t drop it I’ll shoot.’ He dropped it. I told him then to unbuckle his sabre belt and hand it to me. He did so. I buckled it around me with scabbard and pistol that were on it. I ordered him to dismount which he did and to hand me his sabre which I returned to its scabbard. I then took him back up the hill, he holding to my stirrup leather….”

J.R. Crawford, who was a witness to the event, noted: “Maj. Holmes Conrad, of Gen. Ashby’s staff, rode swiftly, and demanded his surrender; but Sir Percy at first defiantly twirled his sword as though he were ready for combat. But Major Conrad rode close to him, with his pistol ready to pull the trigger, and Wyndham, seeing that Conrad had the ‘drop’ on him, said, ‘I am your prisoner,’ and handed Conrad his handsome sword which Garibaldi had given him. Major Conrad holds that sword as evidence that he alone captured Col. Wyndham….”

A Federal horseman recalled: “This officer was an Englishman, an alleged lord. But lord or son of a lord, his capacity as a cavalry officer was not great. He had been entrusted with one or two independent commands and was regarded as a dashing officer…He seemed bent on killing as many horses as possible, not to mention the men.”

The Englishman who had boasted he would “get” Ashby, failed to achieve his boasted threat. The turnabout capture would cause a considerable stir on both sides. Major Roberdeau Wheat of the Louisiana Tigers, upon spotting Wyndham, embraced the embarrassed captive, exclaiming, “Percy, old boy!” The two of them knew each other, having served together under Garibaldi in Italy.

In the years since the war several men would claim credit for the capture of Percy Wyndham. Some would say Turner Ashby had accomplished the feat himself. Jacob Crisman, a Frederick County farmer and veteran of Ashby’s cavalry, would claim credit for the feat as well. Still, the most accepted account of the event was that of private Conrad.

In the fighting that would take place here later that day, at a battle variously named the Battle of Harrisonburg, Chestnut Ridge, and Good’s Farm, the combat would prove costly for the Confederacy. Though the skirmish would be a victory for the Confederates, with Ashby’s men capturing a battle flag, and more than 60 prisoners, Turner Ashby would have his horse shot out from under him while resisting an attack by a detachment of Pennsylvania Bucktails. Back on his feet he was immediately struck by a bullet and killed. Some said he may even have been the victim of friendly fire. His body would be quickly removed from the battlefield and taken to the home of Frank Kemper in Port Republic.

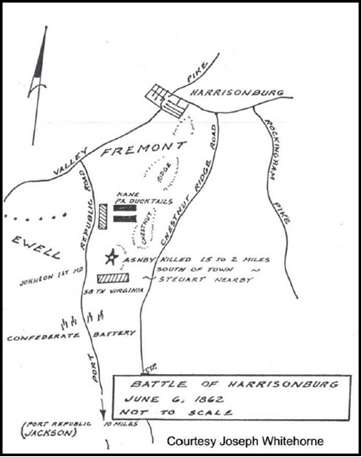

Map of the Battle of Good’s Farm or Chestnut Ridge

Wyndham’s stay in Confederate hands would be brief. He was paroled shortly after his capture, but he was not exchanged until mid-August. After Wyndham’s swap he returned to the 1st New Jersey Cavalry where he would lead his regiment at the Battle of Thoroughfare Gap in August, 1862. At 9:30 a.m., on August 28, Wyndham’s troopers encountered Longstreet’s vanguard while attempting to fell trees across the road on the east side of the gap. Though Wyndham dispatched a courier for reinforcements he was forced to meet the Confederate advance alone. Outnumbered and outflanked Wyndham was soon driven from the gap. As a result, Longstreet’s Corps was allowed to join Jackson at 2nd Battle of Manassas.

Later that year Wyndham was promoted to brigade command, which included his own 1st New Jersey, the 12th Illinois, 1st Pennsylvania, and the 1st Maryland Cavalry. In early 1863, while his brigade was headquartered at Fairfax Court House, Wyndham was given the task of running down John S. Mosby’s guerrillas. Wyndham had publicly insulted Mosby by referring to the Confederate partisan’s men as “a pack of horse thieves.”

The accusation incensed the Confederate cavalryman. In retribution, Mosby decided a personal response was in order. When a deserter from the 5th New York Cavalry disclosed the location of Wyndham’s headquarters, Mosby decided he would launch a raid on the town.

On the night of March 9, 1863, Mosby entered the heavily guarded town a little after 2 a.m. in order capture Wyndham. Unfortunately, Wyndham had gone into Washington for the evening and was spared the humiliation of being captured for a second time. Still, Mosby bagged the slumbering Brigadier General Edwin Stoughton, a number of infantrymen, and a quantity of horses.

Subsequently, Wyndham’s application for promotion to Brigadier General was denied. The denial occurred following a fellow officer’s accusation “of disloyalty and of considering transferring to the Confederate Army.” Though Wyndham would continue to draw his army pay for some time, he retired from Federal service on July 5, 1864.

Nevertheless, soldier of fortune Percy Wyndham would prove to be an extremely interesting character in world military history. At the age of fifteen he entered the French navy, serving as a midshipman during the French Revolution of 1848. He then joined the Austrian army as an officer and left eight years later as a first lieutenant in the Austrian Lancers. He resigned his commission on May 1, 1860 to join the Italian army of liberation being led by the famed guerrilla leader Giuseppe Garibaldi. He received a battlefield promotion to major at the Battle of Milazzo, Sicily on July 20, 1860 and was later knighted.

Wyndham took part in a number of ventures following the Civil War. He relocated to Calcutta, India, and later to Rangoon, Burma. On February 3, 1879, his obituary appeared in the London Times. In part it read: “News of a sad accident comes from Rangoon. Colonel Percy Wyndham, a gentleman well known in Calcutta and Rangoon, announced an ascent in a balloon of his own construction. After attaining a height of about 500 feet the balloon burst, and the unfortunate aeronaut fell into the Royal Lake, whence he was extricated quite dead.”

Holmes Conrad would also survive the war. In 1865 Conrad commenced the study of law in his father’s office in Winchester, and on his admission to the Virginia bar in January 1866, joined his father’s practice. In 1878, he was elected to the Virginia legislature, serving until 1882. Over the next few years, he became a prominent member of the Virginia bar and acquired an influential position in the the Democratic Party. In 1893 President Grover Cleveland appointed him Assistant Attorney General of the United States, and in 1895 he became Solicitor General. Following his death in 1915, he was buried in Mt. Hebron Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia.

Sources:

Sherwood, W Cullen and Ritter, Ben. Americas Civil War. November 2006.

Wert, Jeffry. Mosby’s Rangers: The True Adventures of the Most Famous Command of the Civil War. Simon and Schuster Paperbacks. New York. 1990.

Winchester Evening Star. Edward H. McDonald. May 1904

http://civilwarcavalry.com/?p=665

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Percy_Wyndham_(soldier)

https://cenantua.wordpress.com/2011/07/16/three-conrads-from-winchester/

Hi Pete –

Thanks for another great article – extremely interesting!

Do you know of anyone willing to function as a private guide at the Murfreesboro National Battlefield Park? Our recent inquiries with the Park officials and local chamber of commerce have been unsuccessful.

Hope you and your family are doing well.

Otis Fox

LikeLike

Hello Otis I don’t know anyone that conducts tours at that battlefield. I checked with a couple of friends and they don’t either. Surprised the visitors center doesn’t either. We are all healthy here. I trust you are doing well too. Take care. Pete

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Well researched and written, Peter. Wyndham blew a “win” at Brandy Station when he hesitated before charging FleetwoodcHill, in my opinion.

LikeLike

Pete, Enjoyed your article on Sir Percy. He definitely had a flamboyant personality and would be hard to forget. Quite the character. Well done. 👍 Glenn

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Great information! Of course Percy would check out of the world in a most spectacular manner. Go for it Percy!!!

LikeLike