In early February 1863, a young Maryland native named George Pforr, journeyed from Baltimore, Maryland to his sister’s home in Staunton, Virginia. Professing Confederate sympathies, George felt drawn to support the Southern war effort. It is here that he meets Captain John H. McClanahan and decides to join a newly formed artillery battery which had been christened McClanahan’s Mounted Artillery. The unit is promptly assigned to support the 62nd Regiment of Mounted Rifles, and General John Imboden’s independent cavalry command in the Shenandoah Valley.

Pforr would participate in the famed Jones-Imboden Raid into West Virginia in April and May 1863. Raiders claimed success as they severely damaged several railroad bridges, an oil field, and destroyed other critical Union infrastructure. Attackers also captured valuable supplies. General Jones estimated that about 30 of the enemy were killed and some 700 prisoners were taken. Four hundred new recruits were added to their ranks, as well as an artillery piece, 1,000 head of cattle, and some 1,200 horses. From a political standpoint, however, the raid failed, for it had no effect on pro-statehood sentiment. West Virginia was admitted into the Union as the 35th state the following month.

During the Gettysburg Campaign, Imboden’s brigade served under Major General J.E.B. Stuart guarding the left flank for General Robert E. Lee’s Army during his drive north through the Shenandoah Valley. Though his brigade did not participate in Stuart’s foray around the Union Army, it instead raided the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad between Martinsburg, West Virginia, and Cumberland, Maryland.

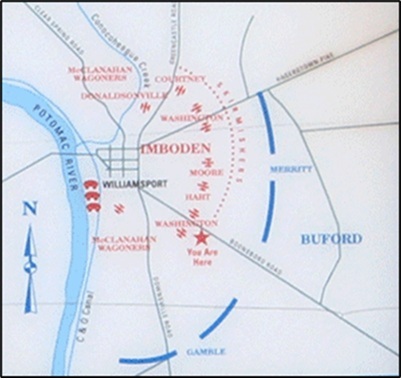

During the Battle of Gettysburg, General Imboden’s men remained in the rear guarding ammunition and supply trains. Throughout the Confederate retreat, though, Imboden was ordered to escort the army’s wagon trains, containing thousands of wounded soldiers, back to Virginia. On July 6, 1863, with the Potomac in flood, he found himself trapped with his wagon train at Williamsport, Maryland. Imboden hastily put together an effective fighting force which included McClanahan’s Artillery Battery, and those wounded soldiers who could still manage a musket. This hurriedly organized force turned back several attacks from Union cavalry details under both Generals John Buford, and Judson Kilpatrick. Imboden’s efforts saved the wagon train and thousands of wounded soldiers from capture. Robert E. Lee would praise him for the way in which he “gallantly repulsed” these attacks.

Imboden’s Defense of the Wagon Trains at Williamsport (Civil War Trails Map)

General Imboden returned safely to the Shenandoah Valley, bringing thousands of Union prisoners and Confederate wounded with him. The general would continue to fight in the Shenandoah Valley serving as a major distraction to General Mead’s Army in eastern Virginia. George Pforr, and McClanahan’s Battery, would minister admirably to this cause.

In turn, on February 27, 1864, Charles W. Anderson, during one of the most severe cold spells to ever hit the Shenandoah Valley, rode to Kernstown and into the camp of the 1st New York Cavalry, also known as the Lincoln Cavalry. “The slightly built man reins his horse up in front of the regimental headquarters tent. To the soldiers idling in front of the tent he says he wants to enlist.” Though the regiment has its origin in New York City the unit has “members from throughout the Union, with one company from Pennsylvania, and another from Michigan. The regiment had been in the field continually since early 1861, and it was not uncommon for civilians to walk up and offer to join the regiment.

The regiment’s Sergeant Major greets Charles. With the weakened state of the cavalry regiment, all the companies in the unit desperately need replacements. Here was “a healthy-appearing young man who even has his own mount.” Charles claimed that he was born in New Orleans on March 15, 1841. He is 5’ 7” with grey eyes and black hair. “He says he is a local farmer who has stayed out of the war until Rebels foraged through his land, stealing crops and livestock. Now he wants revenge.”

The sergeant Major was initially suspicious of the recruit. “It is obvious the man’s hair is dyed and he doesn’t sound like he is from Louisiana. Still, he extends his hand and says, ‘Welcome to the 1st New York.’” Sign on the dotted line my friend. Charles Anderson is quickly registered and assigned to Captain Edwin F. Savocool’s Company K.

For the next year Private Anderson and his 1st New York Cavalry spar with Confederates up and down the Shenandoah Valley. “Anderson proves himself a competent, able soldier. Not foolhardy, he none the less pushed boldly forward while others hold back. He quickly develops a well-deserved reputation for coolness under fire.”

May 13, 1864, Cavalry Clash at New Market. (Peter Dalton)

On May 13, 1864, Private Anderson and his comrades experience a disastrous encounter at New Market. Among the Confederate units on the field is McClanahan’s Battery. The confrontation with Colonel William Boyd’s New Yorker’s is ruinous, and losses are significant. “The wonder was that the whole of Boyd’s command was not captured. Hemmed in between mountain and river, with superior forces on all sides, it was individual determination that saved those that escaped.” Colonel Boyd lost more than 125 men. The majority of these were captured. Most of the rest were left hiding on the slopes of Massanutten Mountain. Nearly 200 horses were secured, all of which would serve as much needed replacements for worn Confederate mounts. Charles Anderson was fortunate to escape.

The fighting was virtually constant throughout the remainder of 1864. During the 3rd Battle of Winchester Charles fought in General William Averell’s Division and was part of the largest Cavalry charge of the Civil War. During the burning of the Valley, he helped destroy farms in the Page Valley from Port Republic to Front Royal. He was also present for the last major battle in the Shenandoah Valley at Cedar Creek.

On February 27, 1865, however, General Philip Sheridan decided to shift his army from Winchester, south, with the intention of joining General Grant at Petersburg. It was Sheridan’s goal to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad as well as the James River Canal system. Opposing him were the remnants of the Army of the Valley District under General Jubal Early.

On March 2nd, with Union Cavalry leading the advance of the army, General George Custer collided with videttes from Early’s Confederate forces near Fishersville. Custer quickly dispersed this contingent and pushed them back into Waynesboro where General Early determined he would make his stand.

General Early had chosen his defensive position badly. General George Custer quickly pushes into Waynesboro and orders an immediate assault without waiting for a reconnaissance of the enemy position. Custer sends three regiments, including the 1st New York, into the woods on the Confederate left flank. His other two brigade’s faceoff directly opposite General Early’s main battle line.

At 3:30 pm, the signal to attack was given. “A section of Custer’s horse artillery rolled into action and engaged the attention of the Confederates. Minutes later, Pennington’s flanking force, led by the 2nd Ohio, dismounted, and armed with Spencer Carbines, rushed out of the woods and rolled up the startled Confederates’ left flank.” “Just as the Confederates were reforming to face this new threat, Wells’ and Capehart’s brigades rushed the Confederate center. In a matter of minutes, Early’s army was thrown into panic.”

Modified Hotchkiss Map of the Battle of Waynesboro

Among the men charging in on the Confederate left flank is Private Charles Anderson. “Riding hard through the rain-soaked timber Anderson spurs his horse onward. He bears down on a Rebel color guard, gives a yell, and fires his revolver into the air. Anderson grabs the enemy flag. He pulls it toward him. A brief tug-of war ensues. Anderson wins. He quickly stuffs the Confederate flag into his shirt and rejoins his comrades in rounding up enemy stragglers.”

Jubal Early and his forces are stunned by the weight of the attack. The Confederate line breaks and collapses. In the fighting that ensues more than 1800 men are captured, along with 200 wagons, 14 artillery pieces, and 17 Confederate battle flags. While Jubal Early escapes, his small army is destroyed. The victory is complete. Jedediah Hotchkiss calls this battle “one of the most terrible panics and stampedes I have ever seen.”

The following week, the cavalrymen who had captured battle flags at Waynesboro were sent to Washington, D.C. On March 19, they are allowed to present their battle trophies to Secretary of War Edward Stanton. It is the largest quantity of battle flags ever captured in a single engagement during the Civil War. As a reward for their bravery each man is given a thirty-day furlough and awarded the Medal of Honor.

When Charles Anderson finally rejoins the 1st New York, General Robert E. Lee has already surrendered his army at Appomattox. A few days later the 1st New York is sent to Washington to be mustered out. “On June 27, 1865, with a Medal of Honor in his pocket, Charles receives an honorable discharge.

Anderson determined he is going to trek back to Baltimore to seek employment. Charles finds job hunting very discouraging and disappointing. Without any apparent employment prospects, he decides he will return to the occupation he knows best. He impetuously enlists in Company M (Maddog Troop) of the 3rd U. S. Cavalry on January 11, 1866.

Charles will spend the next twelve years battling Indians in the Desert Southwest and on the Northern Plains. He will fight against the “Mescalero Apache, Jicarilla Apache, Navajo, and Ute Indians in New Mexico.” On March 17, 1876, elements of the 3rd Cavalry would fight at the Battle of Powder River. The 3rd US Cavalry was forced to withdraw when frostbite crippled their ranks. Sixty-six troopers suffered from this condition, including Charles, who suffers a frostbite injury to his nose.

During the summer of 1876, the regiment will also participate in the Little Big Horn Campaign against Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. Following General Custer’s infamous defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn, General George Crook would lead an expedition to chasten the perpetrators of the massacre. “Assembling a force of infantry, cavalry, and native scouts, Crook set out with insufficient rations.” This would lead to “one of the darkest chapters” in the history of the 3rd Cavalry, the “Horsemeat March.” “Cavalrymen were forced to eat their horses, their shoes, and anything else they could find.” The march came to end near Slim Buttes, South Dakota where they caught up with the Sioux and defeated them decisively.

After twelve years of “fighting Native Americans, poor rations, and disease,” Anderson decided he has spent sufficient time in the army. He writes to his sister, who lives in Staunton, Virginia, and requests she apply to the army on his behalf for a hardship discharge. Her efforts are successful, and Charles receives his release on April 4, 1878.

With absolution in hand, Charles travels back to Staunton to the home of his sister. Anderson determines he will settle in Staunton and decides to change his name back to George Pforr. That same year, on September 18, he marries Sally Smith Garber. Farmer, and soon to be father, Pforr sets down roots and becomes a praiseworthy member of his community. He and his wife will raise eleven children to adulthood over the next several years.

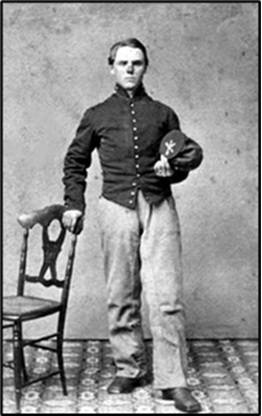

Photo of George Pforr, AKA Charles Anderson. George froze his nose while serving in the 3rd U. S Cavalry. Notice the discoloration of his nose in the above photo.

In 1905 George decided to apply for a federal pension for the time he served in the Federal Army. In his application he claims that he was born in Baltimore, Maryland. He admits that when he joined the war effort, he first enlisted in Captain Jonathan McClanahan’s Confederate Battery. He acknowledges that in February 1864, he deserted his Confederate unit and rode north to where he volunteered to serve in the 1st New York Cavalry. Sergeant James W. Blackburn, formerly of McClanahan’s Battery, confirmed Pforr’s story.

Based on accounts confirmed by soldiers in both armies, George Pforr, AKA Charles Anderson, was awarded a pension in 1906. His name, though, is listed as Charles W. Anderson according to U. S. army records. His Medal of Honor citation, awarded to him on March 26, 1865, reads: “Capture of unknown Confederate flag.”

Charles W Anderson, also known as George Pforr, died on the 25th of February 1916 at the age of 71, at his farm in Annex, Virginia. He is buried in the Thornrose Confederate Cemetery in Staunton. Charles was one of seven 1st New York Cavalry soldiers to be awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery during the Civil War. While his memorial marker reads George Pforr, the Medal of Honor plaque reads Charles W. Anderson, AKA George Pforr. George is, and remains, the only enemy deserter in U. S. military history to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor. He has the only Medal of Honor memorial stone, anywhere, with the letters AKA on it. It is the only burial plot in Thornrose Confederate Cemetery in Staunton, Virginia, or in any Confederate cemetery in the United States, that has a Medal of Honor soldier buried within its boundaries. Now you know the rest of the story.

George Pforr’s Memorial Stone

Charles Anderson’s Medal of Honor Stone

1st New York Cavalry roster.

ANDERSON , CHARLES.—Age , 21 years. Enlisted February 27, 1864, at New York city; mustered in as private, Company K , February 27, 1864, to serve three years; awarded a medal of honor by Secretary of War ; mustered out with company, June 27, 1865, at Alexandria, Va.

Sources:

Blue and Gray Magazine. The Strangest Hero of All. December 1988. Pg. 26.

Driver, Robert J. The Staunton Artillery – McClanahan’s Battery. University of Michigan. 1988.

Stackpole, Edward J. Sheridan in the Shenandoah. The Telegraph Press. Harrisburg, Pa. 1961.

Yes, but the MOH was awarded much more frequently then and for simple valor, not necessarily for courage “above and beyond,” as is the case today.

Tom

LikeLike